When Malware Starts to Behave Like an AI Agent: Shai-hulud 2.0 and a Hypothetical Glimpse Into AI-Industrialized Cybercrime

Before anything else, it is essential to be precise: There is no evidence that Shai-hulud 2.0 uses artificial intelligence models, autonomous agents or AI driven logic. Trend Micro’s research does not make that claim, and nothing in the code explicitly reveals the presence of machine learning components or agentic reasoning. Yet the lack of explicit AI does not diminish the significance of what the report uncovers. In many ways it makes the findings even more relevant. What caught my attention as I read the analysis line by line was not what the malware contains, but what its behavior implies about the trajectory of threat actor capabilities. Sometimes the absence of something is the most revealing detail of all.

After more than two decades studying threat actors, observing their strategies, tracking their evolutions and watching their operations become increasingly industrialized, you develop an instinct for recognizing certain patterns. Campaigns begin to resemble living systems. Workflows mature year after year. Techniques migrate from one group to another. Infrastructure evolves from isolated tools into distributed ecosystems of functions that reinforce one another. Once you have seen enough of these transformations, there are moments when a piece of malicious code reveals a familiar shape, not in its syntax but in its architecture. Shai-hulud 2.0 triggers exactly that feeling. It reads like the early blueprint of something that has not yet fully emerged.

It brings to mind the old saying that if something walks like a duck and quacks like a duck... then perhaps the pattern deserves our attention. Shai-hulud 2.0 is not AI. Or at least there is no evidence of that. And still its behavior resembles an agentic system. Not in the sense of a single autonomous agent carrying out its mission, but rather in the sense of a coordinated set of functions that behave as if multiple specialized agents were pursuing a shared objective. The malware evaluates its surroundings, distinguishes between developer workstations and CI or CD pipelines, alters its behavior based on context, composes tools across cloud platforms, identity frameworks, build systems and software supply chains, and executes its workflow with a degree of fluidity and autonomy that feels more like orchestration than simple scripting.

The malware itself is not AI. Or at least there is no evidence of that. But its architecture is strikingly compatible with what an AI enabled offensive system would require. This is the larger strategic revelation. If this much automation, reach and multi-surface coordination is already achievable today without artificial intelligence, then the leap toward an AI industrialized variant of this kill chain becomes almost inevitable. Attackers would not need to rethink the operation. They would only need to wrap it with AI powered factories, workflow orchestrators and networks of specialized agents capable of maintaining, adapting and scaling each phase of the intrusion at machine velocity. Shai-hulud 2.0 is not an AI driven threat. But it provides a remarkably clear preview of what an AI driven threat will one day look like.

The Invisible Layer Problem: Why AI-Assisted Attack Factories May Never Appear in the Code

One of the most important and least discussed challenges in the coming era of AI-assisted cyber operations is the fact that researchers may never see the AI itself. If Shai-hulud 2.0 were part of a fully AI orchestrated offensive factory, none of the agents, none of the workflows, and none of the autonomous reasoning would necessarily appear in the malware. We would only see the final output: the compiled payload, the packaged scripts, the generated workflows, and the orchestrated steps that the AI has already assembled.

This creates what I call the invisible layer problem. When AI is used upstream in the development pipeline, its fingerprints do not appear in the final artifact. The AI system becomes a black box that produces code, deploys workflows, updates packages, adjusts timing and sequence, and even regenerates infrastructure. Yet when analysts examine the campaign post incident, all they can observe is the end result of that upstream automation, not the machinery that produced it.

This is not unique to malware. In any domain where AI orchestrates multiple components and emits a single coherent result, observers will only see the outcome and not the agentic ecosystem that produced it. It is the same dynamic we see in AI generated text, AI composed images, or AI optimized code. Unless we have access to the generation environment, the underlying agentic stack remains invisible.

This makes attribution of intent especially challenging for AI driven offensive systems. When you analyze only the final artifact, it becomes difficult to distinguish whether a workflow was handcrafted by a human, procedurally assembled by scripts, or dynamically generated by a constellation of specialized AI agents behind the scenes. The malware may show automation, modularity and contextual awareness, but revealing whether this was coded intentionally by a human or synthesized automatically by autonomous agents requires evidence we often cannot access.

This is exactly why we need to think in terms of behavioral patterns rather than literal code signatures. AI enabled orchestration will not announce itself inside the malware. It will reveal itself only through the scale, the coordination, the modularity, the adaptiveness and the multi-surface awareness of the operation. The strategy, not the syntax, becomes the detection vector.

Shai-hulud 2.0 illustrates this challenge clearly. Its architecture behaves like an agentic system, even though the code contains no trace of AI. The workflow feels designed for automation. The orchestration resembles pipelines rather than scripts. The propagation is parallel and modular. The cloud interactions are exhaustive and systematic. All of these characteristics are consistent with an upstream AI assisted environment, even though the AI layer itself would never appear in the reverse engineered output.

If Shai-hulud 2.0 were produced by a full AI factory, we would not necessarily find a single clue in the code. We would only see what we see today: the output of a system that behaves more like an automated offensive ecosystem than a traditional malware family. And this is the deeper conceptual problem we as researchers must prepare for. As AI industrialization accelerates, the real agentic complexity will live above the code, not inside it.

A High-Level View: The Kill Chain and the AI Factory Overlay

Before unpacking the technical mechanics, it is important to approach the Shai-hulud 2.0 campaign from a high vantage point. This operation is not a collection of opportunistic scripts glued together for convenience. It is a coherent workflow that advances in stages, adapts its decisions to the context where it executes, and coordinates actions across cloud platforms, identity systems, developer ecosystems and CI or CD pipelines with a level of structure that is unusual in manually crafted malware. When a campaign exhibits this much sequencing, this much cross-platform sensitivity and this much internal coordination, the question shifts from what the adversary wrote to what kind of system the adversary could be running behind it. After more than two decades observing how threat actors evolve from handcrafted malware to automated toolchains and now to fully industrialized operations, this pattern is unmistakable.

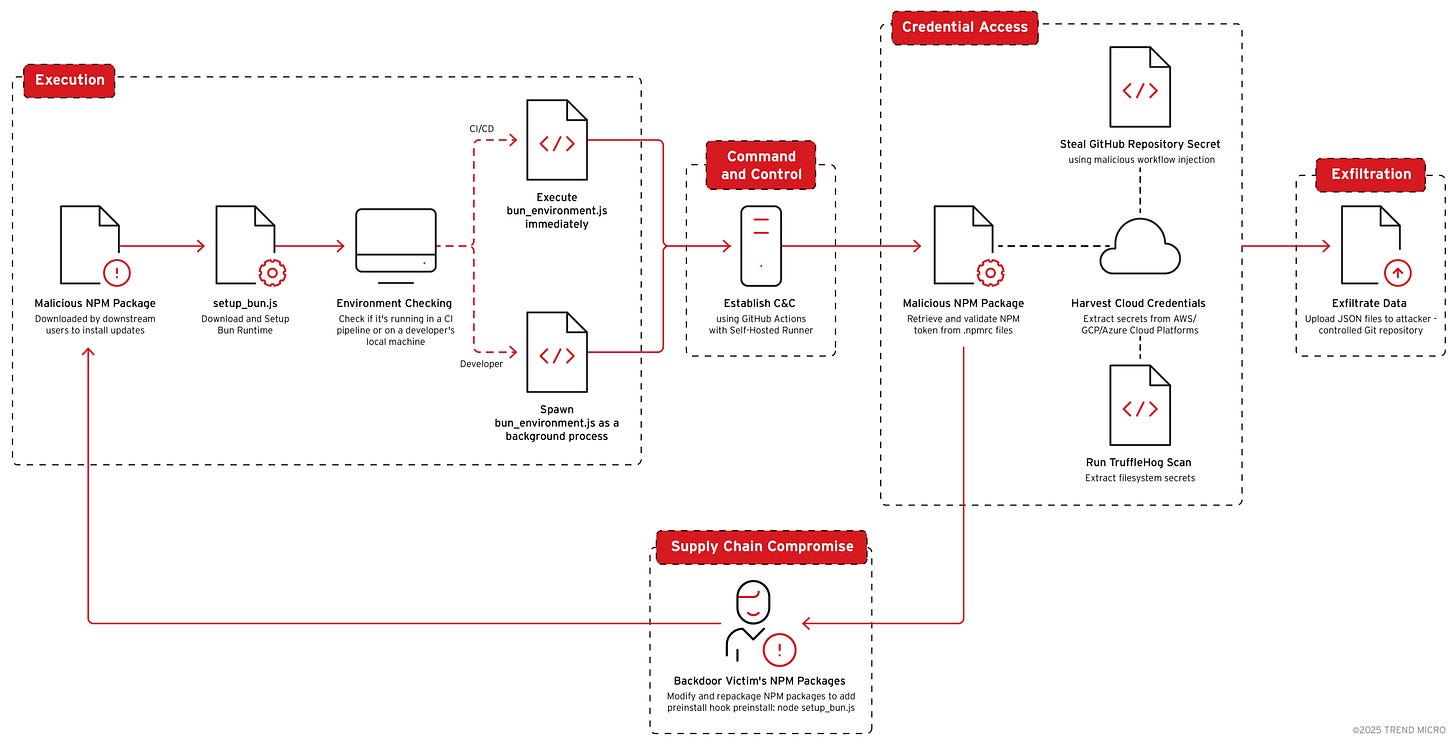

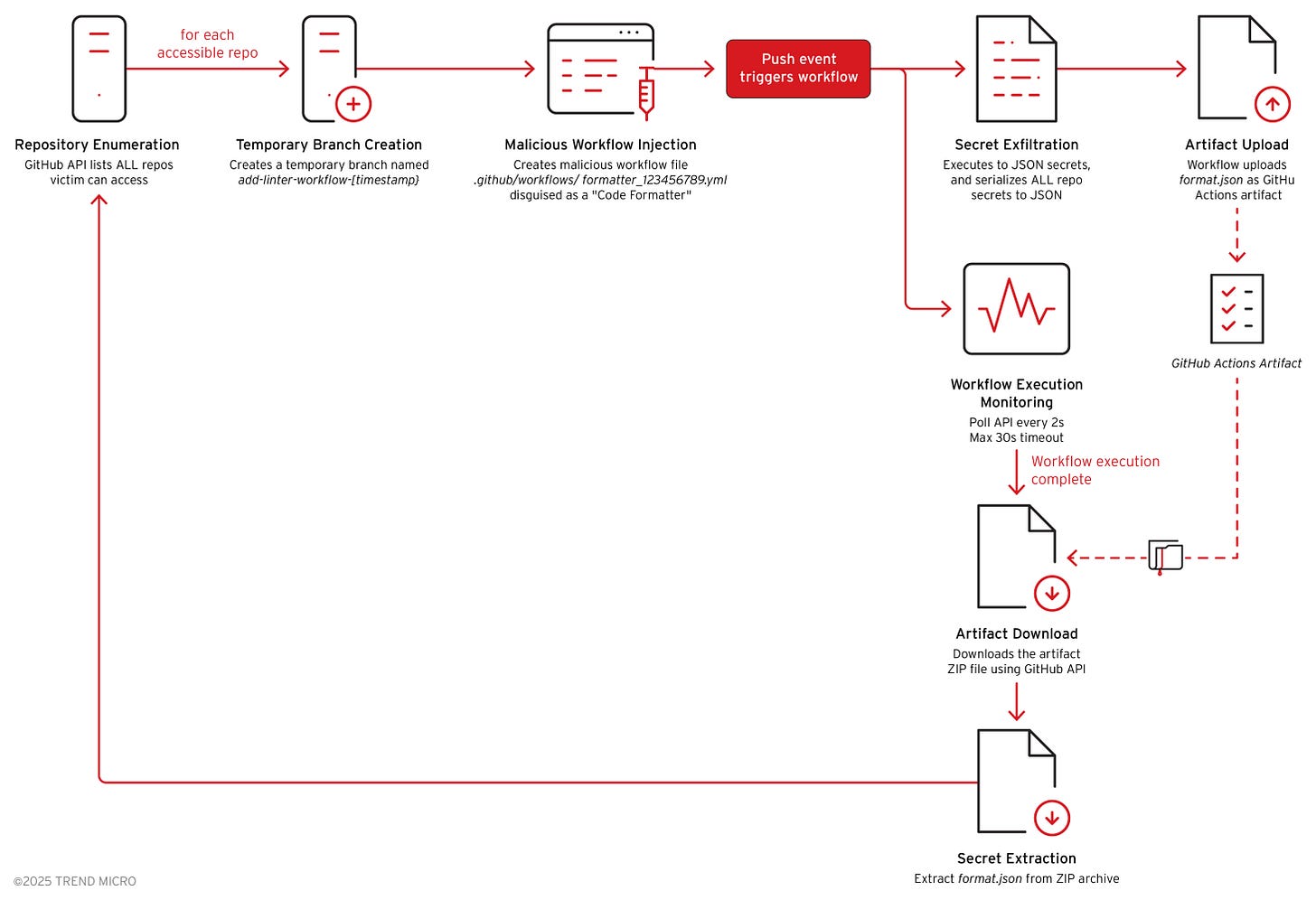

Trend Micro’s analysis breaks the operation into a clear set of phases, which the report captures in its workflow diagram. These stages form a kill chain that includes:

Malicious NPM package as the initial access vector

Loader logic that installs the Bun runtime

Environment detection to distinguish CI or CD pipelines from developer machines

GitHub-based command and control using self-hosted runners

Multi-cloud credential harvesting across AWS, GCP and Azure

Secret extraction from SDKs, environment variables and metadata endpoints

Structured JSON exfiltration to attacker-controlled repositories

Automated NPM republishing to infect downstream dependents as a supply chain worm

When viewed through an AI lens, these phases look less like a linear sequence and more like the modules of an automation pipeline. They are context-sensitive, modular, parallelizable and adaptable. This is the architecture that can easily sit beneath an AI-driven offensive factory. The malware itself is not AI, and there is no evidence that suggests it is, yet the workflow is entirely compatible with an agentic system that could maintain, adjust and regenerate each stage without human intervention.

When I mapped this kill chain against what an AI-enabled adversary could construct, I hypothesized, imagined and ultimately devised seventy-four potential agent roles distributed across eight strategic categories. These categories are not speculative for the sake of speculation. They emerge directly from the structure and sequencing documented in the Trend Micro report, and they reflect how an industrialized AI-powered ecosystem could execute, sustain and evolve a campaign of this nature with minimal human intervention. Each category represents a cluster of capabilities that could be automated, optimized and chained together inside an offensive AI factory:

Category 1 – Targeting and Reconnaissance (12 agents)

Category 2 – Loader and Bootstrap Automation (6 agents)

Category 3 – Cloud and Identity Harvesting (6 agents)

Category 4 – CI/CD Pipeline and Command-and-Control Workflow (7 agents)

Category 5 – Supply Chain Propagation and Worm Expansion (8 agents)

Category 6 – Data Curation, Normalization and Prioritization (3 agents)

Category 7 – Evasion, Mutation and Polymorphism (14 agents)

Category 8 – Orchestration and Meta-Control (18 agents)

This is precisely why Shai-hulud 2.0 matters far beyond its immediate operational footprint. The kill chain documented by Trend Micro captures what we can observe today, the visible mechanics of the current malware. The agent categories, by contrast, illustrate the type of invisible infrastructure an adversary could place behind these mechanics tomorrow. The first is the outward behavior of the campaign. The second is the industrialized factory that could animate that behavior at scale. And once we recognize that this much automation is already possible without artificial intelligence, the distance to a fully AI-driven version becomes less a question of technological feasibility and more a matter of adversarial intent.

Phase 1 - Initial Access: Where a Targeting Agent Would Operate

The entry point of a campaign is rarely accidental. Threat actors do not simply stumble into the accounts they compromise; they select them with precision. After years spent analyzing intrusions, one pattern has remained strikingly consistent across the evolution of threat groups: the targeting phase is where the most intelligence, research and deliberation is invested. Initial access is where attackers make their highest-leverage decisions. When a campaign compromises the exact maintainer whose package unlocks the widest downstream blast radius, the behavior resembles not random exploitation but goal-oriented reasoning. It mirrors the type of selection an AI-driven targeting agent would perform, even if no such agent exists in the current code.

What the malware does today

Compromises an NPM maintainer account

Publishes a malicious package update that appears legitimate

Executes a preinstall hook to trigger its loader at install time

These actions form a classic initial-access pattern, but the precision of the maintainer selection reveals a deeper logic. The attacker chose a maintainer whose packages unlock large dependency graphs, meaning that compromising a single account yields a multiplicative downstream effect. That is the kind of decision adversaries normally make with significant manual research. It is also the kind of decision that an automated system could replicate at far greater scale, with far greater speed.

What a targeting agent could automate

Identifying maintainers with large or high-value dependency graphs using public registry metadata

Ranking targets using popularity, trust signals and blast-radius models

Generating personalized spear-phishing or credential-harvesting lures tailored to each maintainer’s habits, timezone, language and commit history

Validating stolen or purchased credentials automatically and chaining them into scalable account-takeover workflows

In an AI-enabled ecosystem, this phase would represent the work of a targeting and reconnaissance agent whose job is to ingest registry data, correlate social and behavioral patterns, prioritize which accounts offer the highest systemic leverage, and generate automated access strategies for each one. The malware as documented does not contain such intelligence, but its effects align remarkably well with what such an agent could have produced.

Which Agents Would Act in This Phase

If the Shai-hulud 2.0 kill chain were wrapped inside an AI-driven offensive factory, the following agents and categories would be active during the initial-access stage. These show how the attack could be scaled, optimized, and continuously improved by a multi-agent system.

From Category 1: Targeting and Reconnaissance Agents - These are the core agents for this stage.

Registry Intelligence Agent: Ingests NPM registry metadata, dependency graphs and popularity metrics.

Blast-Radius Modeling Agent: Simulates downstream propagation potential for each maintainer.

Maintainer Profiling Agent: Scrapes commit histories, issue activity, timezones and contributor patterns to refine attack timing and social-engineering angles.

Credential Validation Agent: Tests credentials at scale across NPM and GitHub APIs to identify valid entry points.

From Category 7: Evasion, Mutation and Polymorphism Agents - These agents would assist even before the first execution stage.

Phishing Template Mutation Agent: Generates individualized phishing content that mirrors a maintainer’s communication style.

Infrastructure Rotation Agent: Continuously rotates landing pages, IP addresses and email infrastructure to avoid detection.

From Category 8: Orchestration and Meta-Control Agents - These agents coordinate the global strategy that determines which maintainers to target and in what sequence.

Campaign Orchestrator Agent: Selects optimal targets based on updated dependency-graph analytics and current threat-landscape intelligence.

Adaptive Prioritization Agent: Recomputes target rankings as new package statistics or maintainer behaviors change.

Phase 2 -Loader and Bootstrap: Where Environment Awareness Begins

Once initial access is achieved, the Shai-hulud 2.0 campaign transitions into a phase that is deceptively simple on the surface but reveals a great deal about the architectural intent behind the operation. The loader and bootstrap stage is where the malware prepares the execution environment, installs the runtime it depends on, and sets conditions for the main payload to run smoothly across disparate platforms. This stage demonstrates one of the most striking characteristics of the campaign: the malware behaves as if it anticipates heterogeneity. It expects differences between Windows, macOS and Linux. It expects inconsistent PATH configurations. It expects developer machines and CI systems to behave differently. And it adapts accordingly.

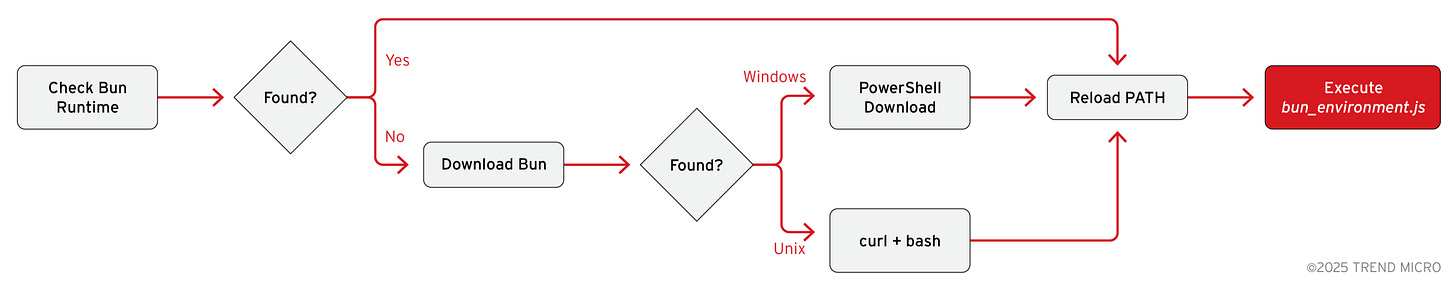

The loader, encapsulated in the setup_bun.js preinstall script, performs several environment-aware steps. It checks whether the Bun JavaScript runtime is already installed. If not, it silently installs it using platform-appropriate commands, mimicking legitimate installation instructions from bun.sh. After installation, it reloads the PATH environment so that the bun executable becomes immediately available, regardless of whether the installation modified the shell configuration or the Windows registry. Only then does it launch the main payload (bun_environment.js), ensuring that execution continues smoothly and unnoticed.

This behavior is notable because it is not merely functional. It is anticipatory. The script includes logic for different operating systems, different shell environments, different PATH propagation models and different privilege levels. It handles errors gracefully. It mimics legitimate installation patterns. It attempts to avoid suspicion through execution timing. These are not trivial details. They are signs of a workflow crafted to maximize reliability across environments that the attacker cannot directly observe. In other words, this is the kind of bootstrap logic that an automation system would generate in order to guarantee consistent execution across a widely distributed victim surface.

What the malware does today

Checks for the Bun runtime across multiple platforms

Automatically installs Bun if missing, using OS-specific commands

Reloads or reconstructs PATH variables to ensure Bun is detected

Locates local Bun binaries if PATH-based detection fails

Executes the main payload (bun_environment.js) once the environment is ready

Each of these steps reflects a nuanced understanding of system diversity. Traditional malware often assumes a narrow execution environment. Shai-hulud 2.0 assumes the opposite. It expects variability and equips itself to navigate it. This is what makes the loader stage feel more like the output of a configuration-aware automation pipeline than a one-off script. If an adversary were using an AI-driven system upstream, this is exactly the kind of component that would be continuously maintained and regenerated.

What a loader or bootstrap agent could automate

Generating OS-specific installation routines for runtimes and dependencies

Adjusting each routine as vendors update installation methods or change scripts

Creating fallback mechanisms for PATH reconstruction and environment discovery

Simulating execution under multiple shells, CI systems and local configurations

Tuning silent execution timing to mimic legitimate toolchain behavior

Rewriting loader logic whenever Bun, Node.js or the underlying OS changes

An AI-enabled ecosystem could rebuild this loader logic continuously. Any breaking change in Bun’s installer, a deprecation in Windows PATH handling, a macOS shell migration, or a new Linux distribution nuance could be automatically incorporated. From the attacker’s perspective, this reduces fragility. From the defender’s perspective, it increases durability. And from a strategic point of view, it transforms the loader stage from a simple utility into an adaptive automation layer.

Which Agents Would Act in This Phase

In an AI-assisted offensive factory, the loader and bootstrap phase would activate agents across several categories. These agents ensure cross-platform compatibility, environment readiness, and robust execution pipelines that survive ecosystem drift.

From Category 2: Loader and Bootstrap Automation Agents - These are the primary agents for this phase.

Runtime Installation Agent: Generates and maintains OS-specific installation commands for Bun.

Environment Discovery Agent: Identifies shell, OS version, PATH configuration and privilege context.

Fallback Logic Agent: Creates alternative execution pathways when PATH or runtime discovery fails.

Silent Execution Agent: Tunes loader timing, outputs and behaviors to avoid detection in developer or CI environments.

From Category 4: CI/CD and C2 Workflow Agents - Although their main action occurs later, they influence this stage by anticipating CI behavior.

Pipeline Context Agent: Simulates how the loader executes inside GitHub Actions, CircleCI, Buildkite and others.

Privilege Surface Agent: Evaluates whether bootstrapping is more reliable in CI systems than on endpoints, influencing loader behavior.

From Category 7: Evasion, Mutation and Polymorphism Agents - These agents ensure the loader stays resilient over time.

Installer Mutation Agent: Periodically rewrites installation logic to mimic current Bun documentation.

Behavioral Cloaking Agent: Mimics legitimate dependency-install patterns to reduce suspicion.

From Category 8: Orchestration and Meta-Control Agents - These agents ensure consistency across the entire campaign.

Execution Reliability Agent: Monitors telemetry from failed deployments and regenerates loader logic automatically.

Cross-Platform Policy Agent: Maintains a repository of execution strategies for different OS and CI environments.

Phase 3 - Environment Detection: CI/CD Versus Developer Workstation

One of the most striking aspects of the Shai-hulud 2.0 campaign is the way the malware distinguishes between its execution environments. This is not a trivial detail and not something commonly seen in commodity malware. It is a sign of awareness. It is a sign of context sensitivity. And in many ways, it is the earliest point where the operation begins to behave less like a script and more like a system. From the moment the main payload (bun_environment.js) launches, the malware evaluates whether it is running inside a continuous integration or continuous delivery pipeline or on a local developer workstation. This decision shapes the rest of the kill chain.

Why does this matter? In modern software supply chains, CI/CD pipelines are privileged environments. They aggregate secrets, tokens, cloud credentials, repository permissions and build-time metadata. They can publish packages, sign binaries, deploy artifacts and initiate infrastructure processes. A single execution inside a CI pipeline yields more value to an attacker than dozens of developer machines. At the same time, developer endpoints provide a natural hiding place. Users expect tools to execute during installation, and background tasks are less suspicious. The dual-environment strategy acknowledges both surfaces and optimizes behavior accordingly.

When Shai-hulud 2.0 detects CI/CD variables such as GITHUB_ACTIONS, PROJECT_ID, BUILDKITE, CIRCLE_SHA1 or CODEBUILD_BUILD_NUMBER, it executes immediately in the foreground. This is deliberate. CI pipelines are ephemeral and time-boxed. Delaying execution risks losing the opportunity to harvest secrets before the job completes. On developer machines, however, the malware detaches itself into a background process using Bun’s spawn().unref() pattern, ensuring that npm install finishes within expected timing and nothing appears broken to the user. The parent process ends quietly while the child process inherits the full environment, including all credentials. It is a strategy designed for stealth, persistence and continuity.

What the malware does today

Inspects environment variables to determine whether it is running in CI/CD or on a developer endpoint

Executes immediately in CI/CD to maximize access to privileged build-time secrets

Spawns a detached background process on developer machines to avoid alerting the user

Inherits environment variables to capture credentials silently

Maintains operational consistency across heterogeneous environments

This behavior is subtle but profound. The malware is not merely reacting to its environment. It is selecting between strategic modes of operation. It understands that a CI pipeline offers high-value credentials but only for a short window. It understands that a developer workstation offers persistence and lower detection risk. And it knows exactly how to behave differently in each scenario. This is not a random branching structure. This is policy logic. It feels designed to maximize the value of every execution context, even though there is no evidence of AI involvement.

What an environment-detection agent could automate

Generating classifiers that detect CI/CD environments across dozens of platforms instead of a handful

Updating those classifiers as cloud providers add new variables or change naming conventions

Simulating execution in virtual CI pipelines to tune timing and ensure operational stability

Adapting the background-process strategy to reflect new endpoint security patterns

Prioritizing different behaviors based on the value of exposed secrets in each environment

Learning from failed executions and adjusting detection logic automatically

In an AI-assisted offensive ecosystem, this phase would be owned by agents specializing in execution-context detection, CI pipeline modeling and behavioral optimization. They would not simply match variables. They would build and maintain a model of hundreds of CI systems, thousands of developer environments and countless runtime variations. The goal would be reliability and stealth, and the malware’s current behavior resembles exactly the type of decision-making such agents would drive.

Which Agents Would Act in This Phase

In an AI-driven factory, the decision to differentiate between CI systems and developer endpoints would activate agents in multiple categories. These agents would ensure the malware adapts its behavior and execution strategy to the environment it encounters.

From Category 1: Targeting and Reconnaissance Agents - These agents provide environmental awareness.

Environment Intelligence Agent: Ingests patterns from major CI and CD platforms and maintains an up-to-date map of environment variables, configuration signatures and metadata patterns.

Surface Valuation Agent: Assigns strategic value to each environment type, determining which secrets are worth prioritizing.

From Category 2: Loader and Bootstrap Automation Agents - These agents stabilize execution across platforms.

Execution Path Agent: Selects between foreground execution in CI pipelines and background stealth execution on developer endpoints.

Context Stabilization Agent: Ensures PATH reconstruction, runtime availability and environment-dependent fallbacks remain consistent across heterogeneous systems.

From Category 4: CI/CD and Command-and-Control Workflow Agents - These agents optimize behavior inside privileged build environments.

Pipeline Modeling Agent: Simulates execution under GitHub Actions, AWS CodeBuild, CircleCI, GitLab CI and others to determine the best moment for credential extraction.

Privilege Extraction Agent: Identifies which secrets and tokens appear at various CI pipeline stages and prioritizes them for harvesting.

From Category 7: Evasion, Mutation and Polymorphism Agents - These agents maintain stealth and reduce detection risk.

Detection Surface Agent: Monitors behaviors that CI engines or developer tools might flag and rewrites execution patterns to avoid triggering alerts.

Stealth Optimization Agent: Tunes process attributes, timing and exit behaviors to blend seamlessly with expected installation or pipeline workflows.

From Category 8: Orchestration and Meta-Control Agents - These agents coordinate decisions and maintain operational consistency.

Mode Selection Agent: Chooses the optimal operational strategy based on environment classification and overall campaign objectives.

Telemetry Feedback Agent: Incorporates outcomes from previous executions to refine environment classifiers and adjust policy decisions dynamically.

Phase 4 - Command-and-Control and GitHub Workflow Manipulation

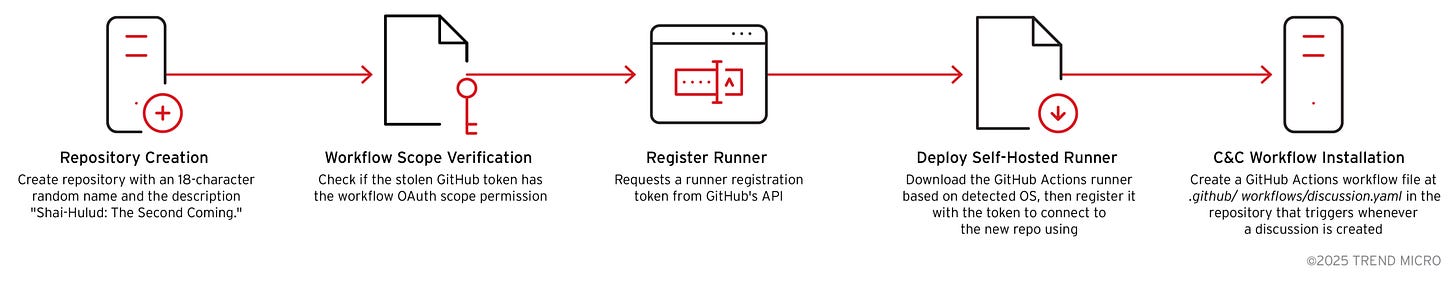

Once Shai-hulud 2.0 finishes establishing its execution foothold, it shifts into one of the most strategically revealing phases of the campaign: the creation of a full command-and-control (C2) infrastructure inside GitHub itself. This step is unusual not because attackers use GitHub, many modern threats do, but because the malware uses the victim’s own GitHub account and privileges to construct a persistent, controlled environment. It creates a new private repository, registers a self-hosted runner, deploys a malicious workflow, and uses GitHub Discussions as a covert communication channel.

This design reveals a mature understanding of developer ecosystems. It blends malicious activity into standard operational behavior by leveraging official APIs, legitimate runner binaries, and native workflow triggers. From a pure mechanical perspective, the malware’s behavior is scripted. But from a structural standpoint, it resembles the orchestration pattern used by autonomous agents coordinating tasks across multiple toolchains. It behaves as though one component “knows” how to build infrastructure, another “knows” how to register a worker, and another “knows” how to exfiltrate secrets through artifacts, even though, in reality, all of this is deterministic code.

This is the moment in the kill chain where the malware stops being a loader and becomes a platform.

What the malware does today

Creates a new GitHub repository under the compromised user

Checks whether the stolen GitHub token has workflow scope permissions

Requests a self-hosted runner registration token

Downloads and configures an official GitHub Actions runner

Deploys a malicious workflow triggered by GitHub Discussions

Uses the workflow to receive commands and exfiltrate data

Injects additional malicious workflows into all accessible repositories

This is not simply “command-and-control.” It is workflow hijacking and infrastructure creation using CI/CD features as the medium.

What an AI-enabled agent system could automate

Generating and updating C2 templates that adapt to API changes in GitHub

Selecting optimal runner architectures based on victim OS profiles

Automating fallback runner registration if permissions are restricted

Generating malicious workflow code that mimics legitimate repository patterns

Detecting which repos have the highest secret density and prioritizing workflow injection

Producing time-distributed workflow commits to evade behavioral analytics

Regenerating workflow identifiers, names, timestamps, and branch patterns to avoid detection

Testing workflow execution automatically through simulated pipeline runs

A single human operator could not maintain this level of adaptive behavior across thousands of victims. An AI-augmented ecosystem, with agents responsible for infrastructure, workflow generation, and execution testing, absolutely could.

Which Agents Would Act in This Phase

From Category 4: CI/CD and Command-and-Control Workflow Agents – These agents specialize in building, manipulating and exploiting CI infrastructure.

C2 Infrastructure Agent: Creates repositories, configures runners, and establishes workflow-based communication channels using official GitHub APIs.

Workflow Injection Agent: Generates malicious workflow YAML that blends into repository conventions, handles secret exfiltration and command execution.

Pipeline Trigger Agent: Chooses optimal workflow triggers (push, discussion, PR open, schedule) based on target behavior patterns.

From Category 3: Cloud and Identity Harvesting Agents – These agents exploit the identity plane once GitHub access is obtained.

Token Analysis Agent: Evaluates GitHub OAuth scopes, determines available privileges and maps reachable assets.

Repository Enumeration Agent: Identifies all repos the token can access and ranks them based on secret density or strategic value.

From Category 5: Supply Chain Worm Propagation Agents – These agents expand the parasitic footprint across ecosystems.

Repo Propagation Agent: Systematically iterates through all repositories and injects workflow-based backdoors or exfiltration mechanisms.

Branch Camouflage Agent: Generates plausible branch names and commit messages to blend with developer activity.

From Category 7: Evasion, Mutation and Polymorphism Agents – These agents maintain stealth throughout the manipulation of CI/CD systems.

Workflow Mutation Agent: Regenerates workflow identifiers, job names, run conditions, and commit metadata to evade rule-based detections.

Runner Obfuscation Agent: Configures runners to appear benign and rotates logs, timing and activity patterns.

From Category 8: Orchestration and Meta-Control Agents – These agents maintain global coherence and strategic direction.

C2 Strategy Agent: Chooses whether to deploy one centralized repo or multiple decentralized repos based on risk signals.

Operational Feedback Agent: Consumes detection telemetry and automatically adjusts workflow templates, API calls and timing strategies.

Phase 5 - Credential Harvesting Across AWS, GCP and Azure

After establishing control through GitHub workflows, Shai-hulud 2.0 pivots into one of the most consequential phases of the entire intrusion: the automated extraction of cloud credentials. This is where the malware stops acting like a supply-chain threat and starts behaving like a cloud-native intelligence collector. Trend Micro’s report shows a sequence that is strikingly methodical. The malware extracts secrets from configuration files, environment variables, metadata endpoints, SDK locations, legacy identity stores, and even executes TruffleHog to sweep local file systems for hard-coded credentials. It then serializes all findings into structured JSON files for downstream processing and exfiltration.

This level of consistency across cloud providers is rare in hand-written malware. AWS, Google Cloud and Azure do not share uniform authentication patterns, yet Shai-hulud 2.0 interacts with all three ecosystems in ways that feel harmonized, modular and extensible. The attacker built a cloud-agnostic harvesting layer that responds to environment cues, invokes the right procedures for each provider and uses a shared extraction model to normalize all credentials.

What makes this phase strategically important is that it illustrates how attackers increasingly treat the cloud control plane as a unified digital territory. The malware’s structure mirrors how an agentic system would approach the problem: detect the platform, select the right harvesting routine, run deep scanning when local secrets aren’t enough and serialize everything for analytics.

What the malware does today

Extracts NPM tokens and GitHub credentials from configuration files

Harvests AWS, GCP and Azure credentials from environment variables, shared config paths and metadata endpoints

Uses cloud SDK conventions to identify and retrieve identity keys

Executes TruffleHog to scan file systems for hard-coded secrets

Serializes all harvested secrets into consistent JSON objects

Prepares for exfiltration to attacker-controlled GitHub repos

This is a multi-cloud credential harvesting framework disguised inside a supply-chain attack.

What an AI-enabled agent system could automate

Generating provider-specific harvesting routines from public cloud documentation

Identifying new cloud identity mechanisms (IAM Roles Anywhere, Workload Identity Federation, OIDC, etc.) and updating extraction logic automatically

Simulating local cloud developer environments to refine detection of credential sources

Ranking harvested credentials by privilege, blast radius and lateral-movement potential

Using reinforcement signals to prioritize the most valuable cloud accounts or service identities

Dynamically running automated scanners (like TruffleHog or custom embeddings-based scanners) depending on environment richness

Normalizing and tagging JSON outputs so downstream agents can classify victim profiles at scale

This is where the concept of an “offensive AI factory” becomes not theoretical but operationally plausible.

Which Agents Would Act in This Phase

From Category 3: Cloud and Identity Harvesting Agents – These agents specialize in discovering, extracting and normalizing cloud secrets.

Cloud Platform Detection Agent: Identifies whether the system is AWS, GCP or Azure based on filesystem paths, SDK presence, metadata endpoints and environment variables.

Credential Extraction Agent: Pulls identity keys from cloud SDK paths, config files, token caches, metadata services and workload identity endpoints.

Secret Scanner Agent: Executes tools like TruffleHog or embedding-based secret detectors to locate hidden keys across the filesystem.

Normalization Agent: Converts AWS, GCP and Azure credentials into a unified schema for downstream scoring and decision-making.

From Category 1: Targeting and Reconnaissance Agents – These agents contextualize the harvested secrets.

Privilege Mapping Agent: Determines the role, scope and potential impact of each cloud identity uncovered.

Access Graph Agent: Builds a conceptual graph of reachable cloud resources and lateral movement pathways.

From Category 5: Supply Chain Propagation Agents – These agents decide how cloud intelligence influences downstream infections.

Expansion Decision Agent: Uses cloud intelligence to choose whether supply-chain propagation should continue, pause or shift to higher-value repos.

Blast-Radius Prediction Agent: Estimates the impact of compromising cloud identities and integrates this into the overall campaign strategy.

From Category 7: Evasion, Mutation and Polymorphism Agents – These agents ensure the cloud harvesting remains undetected.

Behavioral Camouflage Agent: Mimics legitimate SDK access patterns to avoid triggering anomaly detection.

Timing Obfuscation Agent: Schedules cloud API calls and metadata queries to blend with normal developer or CI behavior.

From Category 8: Orchestration and Meta-Control Agents – These agents coordinate the entire credential-harvesting module.

Harvest Strategy Agent: Chooses which cloud providers to prioritize based on privileges detected and historical success rates.

Feedback Loop Agent: Updates extraction patterns based on changes in cloud SDKs, metadata endpoints or detection telemetry from failed executions.

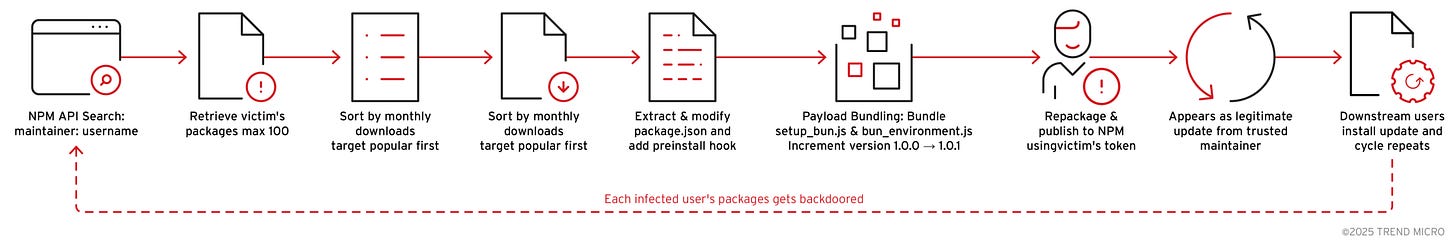

Phase 6 - Supply-Chain Propagation and Package Re-Infection

Once Shai-hulud 2.0 has harvested credentials and established persistence, it transitions into the phase that elevates the campaign from intrusion to ecosystem-level threat: automated supply-chain propagation. This is where the malware stops being a single compromised package and becomes a multi-node worm capable of replicating itself through legitimate developer workflows. Trend Micro’s analysis shows that the malware enumerates all NPM packages maintained by the victim, ranks them, modifies each one by injecting a preinstall hook and republishes them as authentic updates. Downstream developers who install these seemingly routine updates unknowingly become new execution environments, repeating the entire kill chain.

This behavior is profoundly strategic. It mirrors the type of automated expansion logic used in agent-driven systems, even though no such agents exist in the code. Shai-hulud 2.0 is not “learning” or “reasoning,” yet its propagation model behaves as if a planning system is orchestrating the infection path across a graph. It identifies which packages yield the highest replication potential, prioritizes high-download nodes and spreads laterally through dependency relationships, all behaviors consistent with how autonomous agents would scale impact.

What the malware does today

Enumerates all packages maintained by the compromised developer

Retrieves metadata including monthly download counts and package popularity

Sorts packages to prioritize the highest-value supply-chain nodes

Extracts each package, injects a preinstall hook and bundles the loader payload

Bumps the version number and republishes the package using stolen credentials

Produces updates that appear completely legitimate to automated dependency tools

Causes downstream users to unknowingly trigger the entire malware chain

This is a worm inside a software supply chain, operating with precision and purpose.

What an AI-enabled agent system could automate

Predicting which packages offer the highest downstream infection potential using graph models

Generating synthetic but realistic release notes that mimic the maintainer’s style

Detecting patterns in dependency update bots (Renovate, Dependabot) to time malicious releases

Strategically spreading updates over time to evade anomaly detection

Automatically rebuilding packages when NPM changes validation or publishing rules

Simulating dependency trees to estimate propagation outcomes before publishing

Rewriting injected preinstall logic dynamically to evade signature-based detection

Generating version bumps that match historical semantic versioning habits of the maintainer

This is the phase where the imaginary AI factory comes most clearly into focus: a swarm of agents managing ranking, modification, generation, publishing and impact prediction.

Which Agents Would Act in This Phase

From Category 5: Supply Chain Propagation and Worm Expansion Agents – These agents drive automated replication through ecosystems.

Package Enumeration Agent: Queries NPM’s API to list all packages maintained by the compromised account.

Popularity Ranking Agent: Sorts packages based on download statistics, dependency graph centrality and potential blast radius.

Package Modification Agent: Injects the preinstall hook, updates package.json and bundles the loader payload.

Automated Publishing Agent: Rebuilds and republishes each modified package using stolen tokens.

From Category 1: Targeting and Reconnaissance Agents – These agents support intelligent propagation decisions.

Dependency Graph Agent: Analyzes where each package sits within the broader NPM ecosystem to identify optimal infection pathways.

Behavior Forecast Agent: Predicts how downstream consumers will react, including automated updates and caching behaviors.

From Category 7: Evasion, Mutation and Polymorphism Agents – These agents ensure republished packages remain stealthy.

Version Camouflage Agent: Generates semantic version increments that mimic the maintainer’s historical patterns.

Release Notes Agent: Produces realistic change logs matching the tone and formatting of past legitimate updates.

From Category 8: Orchestration and Meta-Control Agents – These agents coordinate large-scale replication activities.

Propagation Strategy Agent: Determines how many packages to modify at once, optimizing speed versus stealth.

Feedback Integration Agent: Monitors detection signals, adjusts publishing cadence and mutates injected logic accordingly.

Phase 7 - Structured Exfiltration: Turning Secrets Into Actionable Intelligence

Every sophisticated intrusion eventually reaches the same critical step: converting harvested data into something an attacker can use. In many traditional campaigns, this stage is crude and noisy, a collection of raw files, memory dumps or screenshots uploaded to a server for later review. Shai-hulud 2.0, however, handles exfiltration with a degree of structure and intentionality that stands out immediately. After harvesting credentials across cloud providers, developer environments and GitHub repositories, the malware organizes all collected data into four well-defined JSON files: contents.json, environment.json, cloud.json and truffleSecrets.json. It then uploads these files as artifacts to the attacker-controlled GitHub repository created earlier in the kill chain.

This approach is not improvised. It is engineered. Each JSON file corresponds to a different dimension of the victim’s operational surface. contents.json captures system metadata and GitHub authentication details. environment.json stores all environment variables, many of which include cloud tokens or developer secrets. cloud.json consolidates extracted AWS, GCP and Azure secrets retrieved from SDK paths, APIs and metadata endpoints. truffleSecrets.json contains hard-coded secrets revealed by TruffleHog. By separating these categories, the attacker makes downstream analysis easier, more scalable and more automatable.

This is where the campaign feels most like a pipeline feeding an analytical backend. Even without AI, the malware acts as if it expects its results to be consumed by automated processes that compare credentials, score privilege levels, correlate cloud identities, identify high-value accounts and propose next steps. None of this is present in the code. But the preparation signals readiness for it.

What the malware does today

Serializes secret classes into structured JSON files

Separates system metadata, environment variables, cloud secrets and TruffleHog findings

Compresses and uploads JSON artifacts to a GitHub repository under the victim’s own account

Uses GitHub Actions Artifacts API to handle secure, authenticated uploads

Ensures exfiltration is embedded within standard CI/CD workflows for stealth

Provides the attacker with clean, well-labeled datasets for manual or automated review

This is disciplined data engineering hidden inside malware.

What an AI-enabled agent system could automate

Parsing and labeling credentials to infer privilege levels and identify high-impact identities

Running classification models to determine which secrets open pathways into production environments

Applying LLM-based inference to detect sensitive patterns beyond standard secret types

Feeding cloud keys into automated permission-graph builders

Generating victim profiles based on correlations between metadata, environment structure and cloud identity maps

Scoring victims across multiple axes: privilege density, supply-chain potential, cloud reachability and CI autonomy

Prioritizing victims automatically and queuing follow-on attacks without human intervention

In other words, while Shai-hulud 2.0 does not contain an AI backend, its output is clearly shaped to feed one.

Which Agents Would Act in This Phase

From Category 6: Data Curation, Normalization and Prioritization Agents – These agents transform raw stolen secrets into actionable intelligence.

Data Structuring Agent: Converts diverse secrets (cloud, local, CI, GitHub) into consistent JSON schemas.

Categorization Agent: Labels secrets by provider, scope and potential impact.

Prioritization Agent: Scores credentials based on privilege level, blast radius and lateral movement opportunities.

From Category 1: Targeting and Reconnaissance Agents – These agents interpret results to update targeting logic.

Victim Profiling Agent: Analyzes exfiltrated metadata to understand the organization’s cloud architecture, CI surface and developer ecosystem.

Target Expansion Agent: Identifies secondary accounts or repos worth compromising next.

From Category 3: Cloud and Identity Harvesting Agents – These agents leverage structured outputs.

Privilege Graph Agent: Maps how extracted cloud identities interrelate inside AWS, GCP and Azure.

Access Path Agent: Identifies routes for lateral movement across infrastructure and account boundaries.

From Category 7: Evasion, Mutation and Polymorphism Agents – These agents keep the exfiltration stealthy.

Artifact Camouflage Agent: Names and timestamps artifact uploads to resemble benign CI outputs.

Data Minimization Agent: Removes noisy or suspicious fields to reduce detection likelihood.

From Category 8: Orchestration and Meta-Control Agents – These agents oversee and optimize the entire data pipeline.

Exfiltration Strategy Agent: Chooses when and how often to upload artifacts, optimizing stealth versus speed.

Feedback Loop Agent: Incorporates downstream intelligence to refine future harvesting and propagation phases.

The Invisible Layer: Orchestration and Meta-Control Agents

If Shai-hulud 2.0 had been produced or operated by an AI-enabled attack factory, the most significant components would not appear in the malware at all. They would exist above it, orchestrating the workflow, sequencing the phases, adapting the strategy and optimizing decisions across the entire campaign. These are the Orchestration and Meta-Control Agents, the invisible command layer that transforms independent actions into a coordinated, evolving system.

These agents never manifest directly in the kill chain. They do not steal credentials, rewrite packages or deploy malicious workflows. Instead, they determine when, how and why those actions occur. They use feedback loops, campaign scoring, detection pressure and environmental cues to steer the entire operation. Because they live outside the artifact, no amount of reverse engineering would reveal their presence.

In an AI-driven offensive ecosystem, this invisible layer would include:

Campaign Director Agent – the architect of the operation: Coordinates kill-chain phases, determines overall sequencing, monitors progress and triggers transitions based on strategic goals.

Adaptive Planner Agent – the strategist: Evaluates the results of each stage, reroutes the campaign when targets yield unexpected value, and reallocates focus toward cloud, CI/CD or supply-chain components depending on opportunity.

Feedback Loop Optimization Agent – the evolutionary engine: Consumes defender IOCs, takedown patterns, detection telemetry and platform changes, then mutates code, workflow identifiers, timing and API calls to maintain survivability.

Temporal Orchestration Agent – the scheduler: Determines timing for payload deployment, package republishing, C2 interaction, dormant periods and staged propagation waves to maximize stealth and impact.

Goal-Scoring & Utility Agent – the prioritizer: Ranks victims, identities, cloud secrets, repositories and potential lateral-movement paths based on calculated strategic value, instructing other agents accordingly.

This orchestration layer is what would make an AI-driven attack not just automated but adaptive, capable of modifying itself continuously in response to signals from defenders, cloud platforms, CI engines, or developer ecosystems. It turns the malware from a tool into a system, from an exploit into an operation, and from a static artifact into a living campaign.

The fact that we do not see such agents in the code does not make them improbable. Their invisibility is precisely what makes them feasible. They would operate upstream from the malware, generating, refining and coordinating components long before they reach the victim’s machine. Trend Micro’s 2026 Predictions report highlights this trajectory clearly, warning that “the line between manual and machine-driven activity is increasingly blurred” and forecasting a world where autonomous orchestration becomes a defining feature of cybercrime’s industrialization.

Shai-hulud 2.0 may not contain these orchestration agents, but the structure of the campaign suggests a workflow ready to be enveloped by them. The kill chain behaves like a chassis awaiting an engine.

How Can We Infer AI Assistance When We Only See the Output?

One of the most difficult questions in modern cyber threat analysis is deceptively simple: how can we know whether an operation was assisted by AI if all we have access to is the final product? Malware is the observable artifact. Workflows are the observable artifacts. Payloads, scripts, configurations and cloud interactions are observable artifacts. But the processes that created them, the toolchains, code-generation pipelines, testing routines, workflow orchestrators, prompt-driven assistants or autonomous agents, are invisible to us. We do not see the factory. We only see what comes out of it.

This challenge is not new in cybersecurity. Analysts have always inferred attacker capabilities from outcomes. When intrusion sets demonstrated coordinated lateral movement or advanced operational security, we inferred disciplined operators. When malware families displayed shared code bases, we inferred common developers. When campaigns deployed custom zero-days in synchronized waves, we inferred resource alignment behind the scenes. The infrastructure was never directly visible, but its fingerprints were everywhere.

The same reasoning now applies to AI-assisted operations. If a threat actor uses an LLM, an MCP workflow, an autonomous agent chain or a code-generation factory to build malware, pentest modules or cloud-harvesting routines, nothing in the resulting code necessarily exposes those tools. The outputs may look like high-quality human work. They may look like structured automation. They may look like modular, well-composed systems. In other words, they may look exactly like Shai-hulud 2.0.

And this is where the analytical challenge deepens. The mere absence of explicit AI artifacts, prompts, embeddings, agent logs, inline comments or model outputs, does not mean AI was not used. AI systems are not like compilers that leave clear signatures. They leave behavioral traces instead: modularity without clear authorship, workflows that are maintained faster than humans can manage, propagation patterns that resemble algorithmic optimization, and design decisions that reflect goal-oriented reasoning rather than opportunistic scripting.

Shai-hulud 2.0 provides an example of this analytical tension. There is no evidence of AI inside its code. Trend Micro’s research makes no such claim. But the architecture, the use of environment-driven branching, the uniform logic across AWS, GCP and Azure, the structured JSON outputs, the deterministic workflow through CI/CD pipelines, the multi-node propagation model, resembles the kind of workflow that AI-enabled systems are increasingly capable of generating and maintaining.

This does not mean the malware is AI-driven. It means the behavior is compatible with AI assistance. And that distinction matters. Just as early Stuxnet analysis revealed a level of engineering that implied a team rather than an individual, modern malware may increasingly reveal levels of automation that imply a factory rather than a coder.

If AI were involved upstream, how would we know? We would not find “AI” labeled anywhere in the code. Instead, we would see signs like:

Logic that evolves faster than typical human update cycles

Components that reflect documentation-aligned patterns rather than developer quirks

Workflows that unify heterogeneous systems under consistent abstractions

Propagation strategies that appear optimized for impact, not opportunism

Modularity that matches how multi-agent systems naturally compartmentalize work

These are the behavioral signatures of an AI-enabled pipeline. They cannot prove AI involvement, but they can suggest it. They form the basis for hypothesis, not attribution.

This creates a new challenge for defenders. The traditional model of analysis, reverse engineering the artifact to infer the actor, becomes increasingly incomplete. If the future adversary is an AI factory, then the “actor” is no longer a person or even a team, but a distributed system of continuous generation. Analysts must learn to detect not just malicious code, but production methods. They must recognize not only threats, but manufacturing patterns. And they must consider not only what malware does, but how it was produced.

This is why the question of AI involvement is not just academic. If adversaries begin to industrialize their operations with AI-driven systems, the output may look deceptively clean, stable, intentional and polished, precisely the qualities that Shai-hulud 2.0 already exhibits without any proven AI. If this much is possible without AI, then the first fully AI-assisted campaign may already be indistinguishable by its outputs alone.

The Road to AI Industrialization Is Already Visible

As we step back from the technical analysis and the speculative architecture that surrounds a campaign like Shai-hulud 2.0, one truth becomes impossible to ignore. The malware itself is not AI, or at least there is no evidence of that. Nothing inside the code suggests the presence of an autonomous model, a planner, or a chain-of-thought system driving its decisions. Yet when we examine its behavior, its sequencing, its cross-platform awareness, and its ability to combine multiple tools into a unified workflow that executes with precision, we observe something that mirrors the behavior of an intelligent agent even in the absence of actual intelligence. This is the paradox that defines the current moment in cybersecurity: attackers do not need AI to behave like AI.

This distinction matters because it is precisely the gap that Trend Micro’s Security Predictions for 2026 warns us about. The report describes a threat ecosystem undergoing rapid AI-fication, where automation, orchestration, and multi-agent workflows are redefining the nature of cyber operations. It explains how “the line between manual and machine-driven activity is increasingly blurred,” and how attackers are reorganizing themselves around infrastructures that allow them to “scale, automate, and coordinate disruption with unprecedented efficiency” . The report goes further, highlighting that agentic AI is no longer theoretical: enterprises already deploy autonomous systems capable of reasoning, planning, calling tools, and executing workflows in multi-step loops. Attackers, naturally, will follow the same path.

When we contextualize Shai-hulud 2.0 within this broader trend, the implications become clearer. The campaign documented by Trend Micro does not require AI to be dangerous. It only needs the architectural compatibility with what an AI-driven ecosystem could become. Its loader resembles a component an agent could regenerate. Its environment detection mirrors the decision-making of a context-aware model. Its cloud and CI/CD credential harvesting aligns with the behaviors predicted for AI-enhanced reconnaissance and exploitation. Its supply chain propagation behaves like an automated worm, ready to be plugged into an agentic pipeline. In essence, the kill chain is already structured in a way that an offensive AI factory could adopt without significant modification.

This is why the argument is not that Shai-hulud 2.0 is an AI-powered campaign. The argument is that it behaves like something that could be, and that this behavioral resemblance is exactly what Trend Micro predicts for 2026. The report warns that AI will not simply assist attackers but will industrialize cybercrime, transforming operations into autonomous, adaptive, multi-step systems that operate across digital and physical environments. It predicts that “modern attacks will be defined not by individual tools or tactics, but by the capacity to scale, automate, and coordinate disruption with unprecedented efficiency” . Shai-hulud 2.0 shows what happens when a non-AI system already begins to approximate that structure.

We therefore reach an uncomfortable but necessary conclusion. If this much automation, coordination, and workflow logic can be achieved without AI, the real pivot point for adversaries is not technical feasibility but organizational intent. The distance between today’s campaign and a fully AI-industrialized version is small, perhaps even trivial. When adversaries can wrap kill chains like this in agentic infrastructures, using AI code assistants, MCP-based tool chains, workflow orchestrators, and autonomous multi-agent systems, the attack surface expands at machine speed. Defenders will not be able to rely on manual playbooks while attackers embrace systems that reason, compose, and act in continuous loops.

Shai-hulud 2.0 is a reminder of the future, not because it uses AI, but because it shows how easily malware can evolve into something that does. And as Trend Micro’s predictions stress, the next era of cybersecurity will not be defined by isolated threats but by the industrialization of offensive capability. Understanding this shift requires thinking beyond code and beginning to think in terms of factories, orchestration layers, and agentic systems. When we do that, the lessons of Shai-hulud 2.0 become clear: we must prepare for adversaries who operate at the tempo of machines, even when the malware we analyze today has not yet crossed that threshold.

Castro, J. (2025). Why 2026 Is the Year That Every Company and Board Must Have a CISO, and Why Every CISO Must Report Directly to the CEO. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/398085286 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.21085.68321

Castro, J. (2025). Artificial Intelligence (AI) vs Artificial Instinct (Ai), The Distinction Cybersecurity Can’t Afford to Ignore. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/397834714 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.31096.30725/1