Cybersecurity: A Strategic Choice and Balance of Trade-Offs for Business Success

At the recent Gartner Security & Risk Summit, a powerful and transformative message emerged, championed by Paul Proctor: cybersecurity is undergoing a revolution in how it’s measured, reported, and invested in. Proctor’s sessions highlighted a critical shift designed to bridge the gap between cybersecurity experts and business decision-makers, moving away from technical jargon to clear, outcome-focused communication and strategic trade-offs. The core idea is that cybersecurity is fundamentally a business choice and a balance.

Paul Proctor uses the Rosetta Stone as an analogy to explain the need to translate cybersecurity concepts for different audiences within an organization. This analogy highlights the challenge of mastering three distinct “languages” and “cultures” to effectively communicate about security.

He describes these three key elements as:

Chief Financial Officer (CFO): Speaking the language of business outcomes. The original work on this new approach was designed specifically for CFOs.

Chief Information Officer (CIO): Speaking the language of supporting technologies.

Chief Information Security Officer (CISO): Speaking the language of outcome-driven value-delivery metrics for cybersecurity.

The goal is to shift the focus towards measuring, reporting, and investing in security outcomes. By doing so, security leaders can “change the language at the bottom so it could pass through the supporting technologies and and talk about the business value of security”. This means connecting the technical details of security (CIO’s domain) and the specific security investments (CISO’s domain, using ODMs) to the financial and strategic priorities that concern the CFO and other executives. The outcome-driven metrics (ODMs) are presented as the mechanism that enables this translation, allowing for executive-level conversations that trade protection levels off with cost.

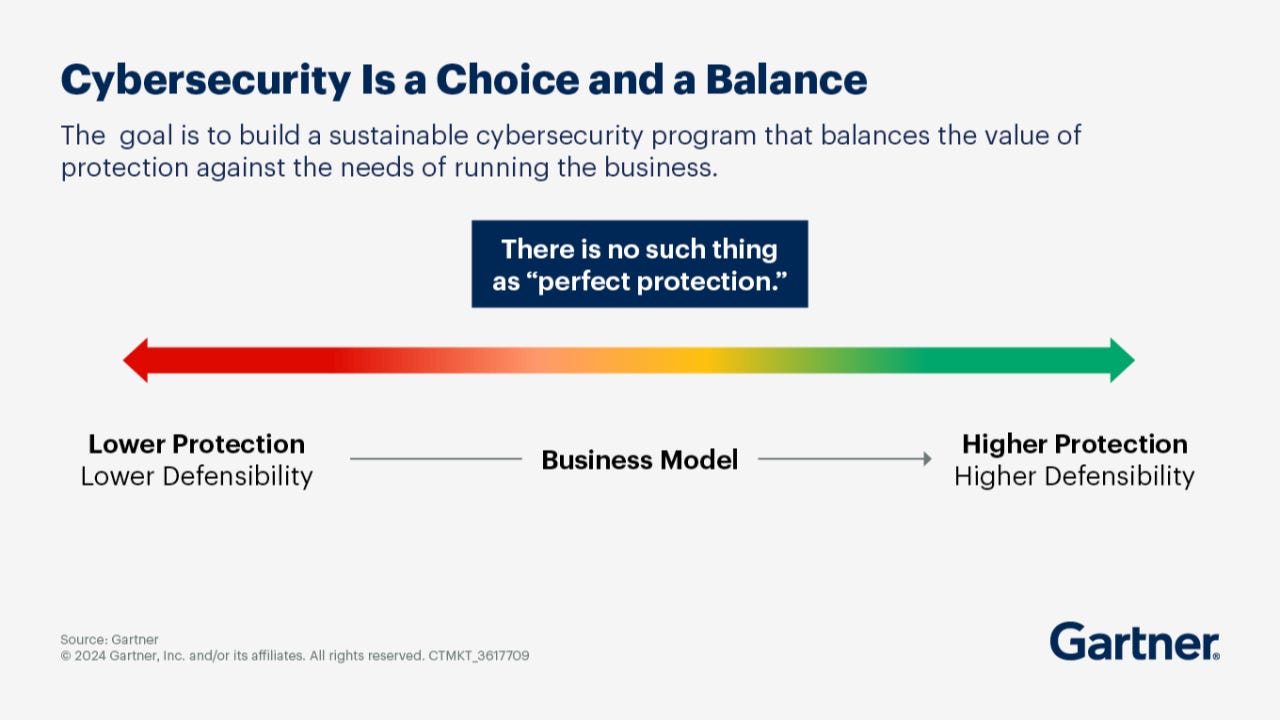

Cybersecurity: No Perfect Protection, Only Strategic Balance

A central tenet of this new approach is the recognition that there is no such thing as “perfect protection” in cybersecurity. Given this reality, organizations must make deliberate choices and find the right balance between protection levels and the needs of running the business. This concept is vividly illustrated as a sliding scale: on one end is “Lower Protection” leading to “Lower Defensibility,” and on the other is “Higher Protection” leading to “Higher Defensibility”. The goal is to strategically position the organization on this spectrum to achieve a sustainable cybersecurity program. This means creating a conversation that explicitly trades protection levels off with cost at an executive level.

Outcome-Driven Metrics (ODMs): Measuring True Protection

To facilitate this strategic balance, Gartner introduced and has been evolving Outcome-Driven Metrics (ODMs). These metrics are distinct from traditional operational metrics because they possess two crucial properties:

When an ODM gets better, the organization is measurably better protected. Conversely, if it worsens, protection measurably decreases.

ODMs act as “value levers”, enabling executive-level conversations that directly link protection levels to costs.

Proctor demonstrated this using the example of patching. Traditional metrics like “number of unpatched vulnerabilities,” “monthly attacks,” or “number of emails that we blocked last month” are considered “worthless” because they don’t directly show achievement or inform future investment. Instead, the critical ODM for patching is: “How fast do we patch our systems?”. This metric has a direct line of sight to patching’s value proposition: reducing the time a vulnerability is available for exploitation. All money spent on patching is to accomplish this one goal. This clarity allows for clear trade-offs: spending more money can lead to faster patching and measurable improvement in protection, while saving money might mean slower patching and less protection. This changes how investment decisions are made and how executives are engaged.

Gartner’s Cybersecurity Business Value Benchmark tool now incorporates 25 such ODMs in its second generation, evolved from an initial 16. This tool, which started as an idea three years ago, now boasts over 700 participating organizations globally across various industries and sizes, providing credible and defensible peer comparisons.

Protection Level Agreements (PLAs): Formalizing Risk Decisions

The concept of ODMs culminates in Protection Level Agreements (PLAs), which Gartner defines as “concrete, measurable, enforceable assertions of risk appetite”. A PLA is a business decision that specifies a desired level of protection and the projected cost to achieve that outcome.

Proctor illustrates this by suggesting security leaders ask their CEO, “How many days would you like our systems available for hacking?”. While the initial universal response might be “zero days,” this is quickly recognized as prohibitively expensive and impractical, and even if an infinite amount of money were available, it wouldn’t make sense due to zero-day vulnerabilities and the need for proper due diligence. This leads to a more realistic discussion of options:

A 7-day patching cadence might cost approximately $5 million a year, which the CEO would likely deem “ridiculously expensive” for a single problem.

A 30-day patching cadence would cost around $1 million a year.

This outcome-driven dialogue facilitates an executive-level conversation that trades protection levels off with cost. There comes a point where the CEO might say, “Let’s do that. I’ll give you a million dollars and you’ll patch our systems in 30 days”. This agreement marks the establishment of a Protection Level Agreement. With a PLA, executives aren’t concerned with how the security team achieves the outcome (e.g., spending the million dollars on people, process, or technology), but only that the agreed-upon protection level (e.g., 30-day patching) is met within the allocated budget. This means literally nobody cares if you have a thousand monkeys running around your data center patching with diskettes, as long as 30-day patching is achieved. This changes how investment decisions are made.

This approach transforms how breaches are perceived. If a system is hacked within the agreed-upon risk level (e.g., hacked in 25 days when the PLA allowed for 30-day patching), it’s understood as the result of a business decision to accept hacks within that 30-day window, not a security failure. This framework provides a “standard of due care”, enabling organizations to defend their protection levels to stakeholders, regulators, and even in shareholder lawsuits, proving they had the “right levels of protection despite getting hacked”. If a system is hacked at 35 days, exceeding the 30-day PLA, it means the security team failed to deliver on the agreed-upon value. This approach allows for self-correcting governance, where if a breach occurs within the agreed-upon risk, executives can decide to invest more for a shorter patching window (e.g., 15-day patching), which they will then need to fund.

The “Real Cost” of Cybersecurity: Beyond the Budget

A significant revelation at the summit was that the security budget rarely represents the majority of the true cost of cybersecurity. To enable proper trade-off discussions and PLA negotiations, organizations must measure the “real cost” of cybersecurity, which encompasses:

IT budget: Capital expenditures (tools, hardware, software) and operational expenses (people, services).

Security budget: Capital and operational expenses for specialized security tools and personnel.

Business friction: Measurable impacts on the business that add to the delivery cost. This can include things like scheduled outages for patching, or productivity loss from security measures like multi-factor authentication (MFA) and annual awareness training. For a 100,000-person company, MFA’s productivity loss alone could equate to 624 full-time equivalent employees (FTEs) annually, and annual security training could be another 48 FTEs. These costs vary greatly by control investment.

Understanding the “real cost” allows for more informed decisions, such as choosing a more expensive security tool if it significantly reduces business friction, making it cheaper overall. It’s crucial to note that this “real cost” calculation is not a budgeting exercise but a tool for PLA negotiation, justifying tool purchases, and aligning security with business outcomes.

The CARE Framework: A Reality Check for Executive Cybersecurity Decisions

To further enhance the alignment between cybersecurity investments and business outcomes, Gartner introduces the CARE framework — a tool designed to help executives evaluate and validate the effectiveness of their cybersecurity posture. CARE stands for Consistent, Adequate, Reasonable, and Effective, and it serves as a pragmatic lens through which to assess whether cybersecurity decisions meet fiduciary, regulatory, and strategic expectations.

CARE is not a checklist — it is a continuous reality check. It ensures that cybersecurity strategies are not only defensible on paper but also aligned with the organization’s actual risk appetite and operational needs. As security leaders embrace Outcome-Driven Metrics (ODMs) and Protection Level Agreements (PLAs), CARE offers the board and executives a grounding framework to guide and challenge those decisions:

Consistent: Are we applying our protection strategy uniformly across systems, geographies, and lines of business? Inconsistencies often signal unmanaged risk or misaligned priorities.

Adequate: Do our chosen protection levels reflect our real exposure and stakeholder expectations? ODMs help answer this by linking protection directly to measurable outcomes.

Reasonable: Can our cybersecurity posture withstand regulatory, shareholder, or legal scrutiny? PLAs establish a documented standard of care, and CARE ensures that standard is reasonable given the context.

Effective: Are our investments and controls measurably improving protection? This is where ODMs shine — demonstrating clearly when controls work, and prompting adjustments when they don’t.

The CARE framework prompts critical executive-level questions:

When is cybersecurity “done”? Never — but it is stable when PLAs are defined, ODMs are met, and governance aligns with CARE principles.

What is the right amount of cybersecurity? It’s the level the business chooses to fund, justified through ODM-driven protection metrics and validated by CARE.

How much should be invested? The cost of cybersecurity is the price of performance. If your PLA is 30-day patching, the budget must support that outcome.

What should the CIO report to the board? A continuous update of ODMs, risk shifts, PLA changes, and how each aligns with the CARE model.

How well are we protected? With ODMs and CARE together, stakeholders gain a real-time, business-aligned view of protection effectiveness.

What is the value of cybersecurity? It lies in its ability to preserve trust, drive performance, enable innovation, and protect strategic outcomes.

By embedding the CARE framework into PLA discussions and ODM reporting, organizations can ensure that cybersecurity doesn’t just “look good” in metrics — but that it actually is good, in terms that matter to boards, regulators, and customers alike. CARE becomes the lens through which cybersecurity becomes business accountability — not just IT responsibility.

Fostering Collaboration and Strategic Impact

This outcome-driven approach is designed to transform executive conversations and foster better collaboration, particularly between CIOs and CISOs. It provides a common language for these leaders, aligning their priorities towards measurable business outcomes. While conflicts between CIOs and CISOs can increase when they report separately, ODMs offer a shared objective for success.

The framework also proves invaluable in various strategic scenarios:

Managing Budget Cuts: Instead of vaguely stating “risk will increase,” security leaders can translate a 10% budget cut into tangible impacts like, “systems will be available for hacking for 15 more days” or “incidents will take 30% longer to stop”.

Mergers & Acquisitions (M&A): ODMs can be leveraged during due diligence to assess the security posture of target companies, informing integration planning, risk considerations, and potential renegotiation of deal terms.

Proctor also highlighted problematic behaviors that perpetuate the misconception that “spending equals protection”. To counteract this, security leaders should always reflect a change in protection level when reporting on tool spending, rather than just reporting the expenditure. They must manage executive expectations, and avoid relying too heavily on spending benchmarks alone to justify budget increases.

In conclusion, Paul Proctor’s message from the Gartner Security & Risk Summit is clear: cybersecurity is a strategic business choice that requires a deliberate balance. By adopting Outcome-Driven Metrics, formalizing Protection Level Agreements, and understanding the “real cost” of cybersecurity, organizations can make smarter investments, communicate effectively with executives, and ultimately create a safer and more defensible world while supporting business growth.