Attackers Only Need to Be Faster Than Our Decision Making Process

Cyber adversaries do not need to outsmart us, outspend us, or out-innovate us. They only need to move faster than we decide. In modern cyber risk, speed has quietly become the dominant advantage, not because defenders lack tools or intelligence, but because organizational decision making remains slower than the threats it is meant to counter. Today’s attackers operate as highly fluid, decentralized networks. They automate aggressively, adapt instantly, and accept imperfection as a tradeoff for momentum. Defenders, by contrast, often optimize for precision, validation, and consensus. This creates a structural imbalance where even correct decisions lose effectiveness simply because they arrive too late to influence the outcome. What makes this especially dangerous is that delay often feels responsible. More data, more analysis, and more certainty are usually framed as good governance. In an adversarial environment, however, waiting is not neutral. Time actively shifts advantage toward the attacker, expanding exposure and reducing the range of meaningful responses.

In my previous article, Cybersecurity Paralysis: When the Cyber Brain of the Organization Breaks, I explored why so many organizations fail not because they lack tools, intelligence, or investment, but because their internal decision-making architecture collapses under pressure. Using the analogy of the human brain, I described how misalignment between analysis, context, and instinct creates paralysis, where organizations think one thing, communicate another, and react far too late.

That earlier work focused on why organizations freeze. This article focuses on how attackers exploit that freeze. While defenders struggle to align analytics, governance, and action, attackers operate as a unified organism driven by opportunity and speed. The gap between those two modes of operation is where modern cyber risk truly lives. This is why so many cyber incidents are not failures of detection or awareness. They are failures of timing. Organizations often recognize the risk, understand its implications, and even agree on what should be done, but they do so after attacker freedom of movement has already expanded. At that point, the decision may still be correct, but it is no longer effective.

At its core, cyber risk is not only about likelihood and impact. It is about how fast an organization can transform signals into meaning, meaning into decisions, and decisions into action. When that transformation is slower than the adversary’s ability to move, attackers do not need sophistication. Speed alone is enough.

The Race for an Effective Decision

Cybersecurity is not a race to perfect understanding. It is a race to decide while the decision still matters. Every incident unfolds as a time-bound competition between attacker action and defender decision making, and the winner is rarely determined by who has more data or better tools, but by who moves first with sufficient intent.

Attackers are always running this race. They do not pause to validate every signal or wait for full certainty. They probe, move, adapt, and accept error as a cost of speed. Defenders, on the other hand, are often structured to slow themselves down. Analysis pipelines, escalation paths, and governance controls are designed for correctness and accountability, not for operating under adversarial time pressure. The result is that defenders frequently arrive at the right conclusion after the moment when that conclusion could still change the outcome.

This is why decision effectiveness is a better lens than decision quality. Quality can improve with time, but effectiveness decays as the attacker continues to act. The race is not about being smarter. It is about staying ahead of the point where additional precision no longer adds value. Once that point is crossed, time switches sides.

In this race, there are three distinct modes of running. The slow, high-quality path tries to win through certainty, but loses ground as time passes. The fast, good-enough path sacrifices some precision to preserve impact. And the pre-authorized path starts the race early, by deciding before the incident begins, so execution can happen immediately when conditions are met. Only the last mode consistently avoids falling behind.

The most dangerous moment in this race is not when defenders make a mistake. It is when they hesitate. Waiting feels responsible, but in a live incident, hesitation is indistinguishable from consent. Every delay gives the attacker more freedom of movement, more optionality, and more leverage.

Winning the race for an effective decision does not require perfect foresight. It requires clear intent, defined thresholds, and the willingness to act under uncertainty while outcomes are still pliable. Organizations that understand this stop asking how to decide better after an incident, and start asking how to decide earlier, before time becomes the attacker’s ally.

In cybersecurity, the finish line is not certainty. It is effectiveness before time runs out.

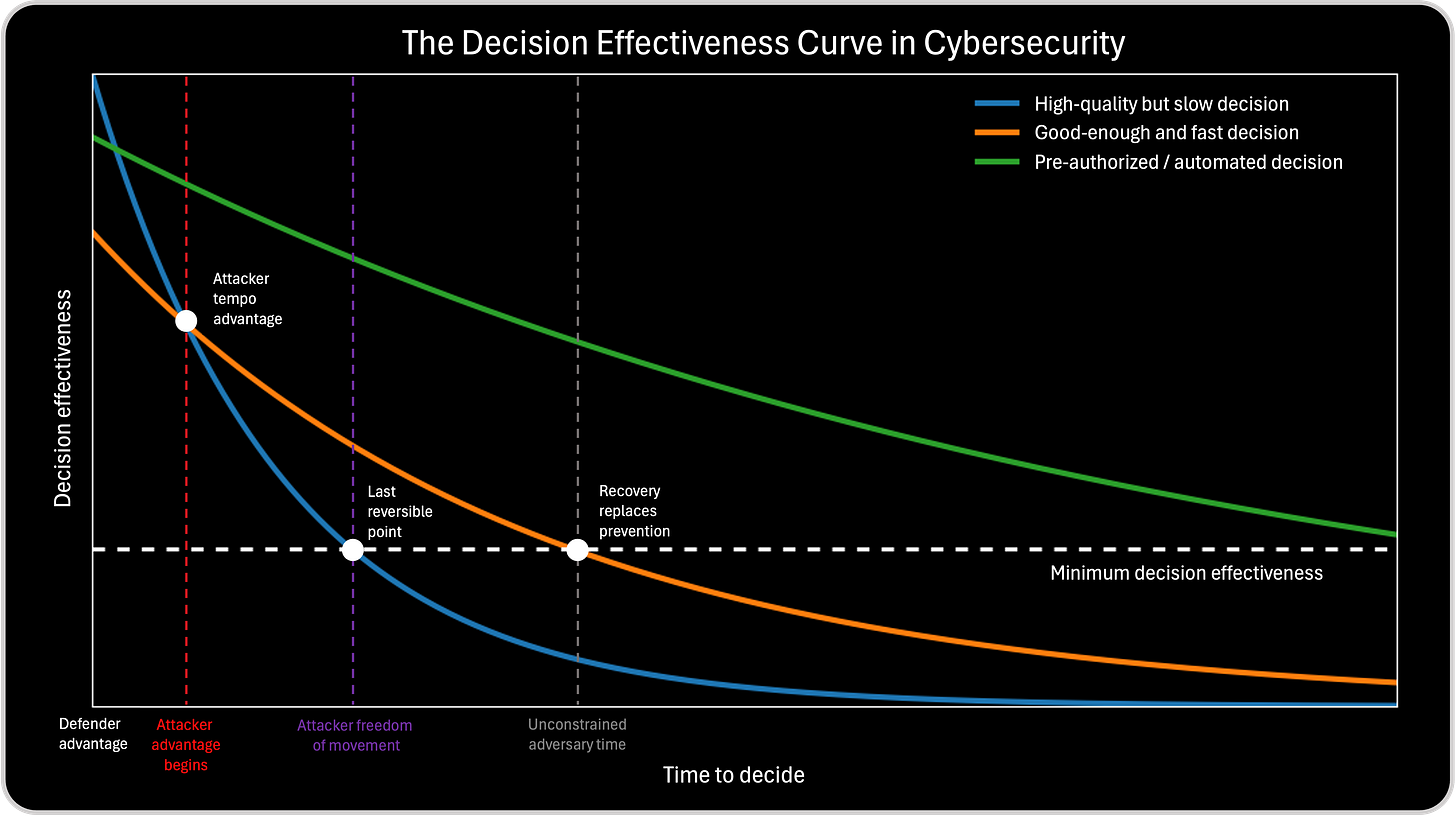

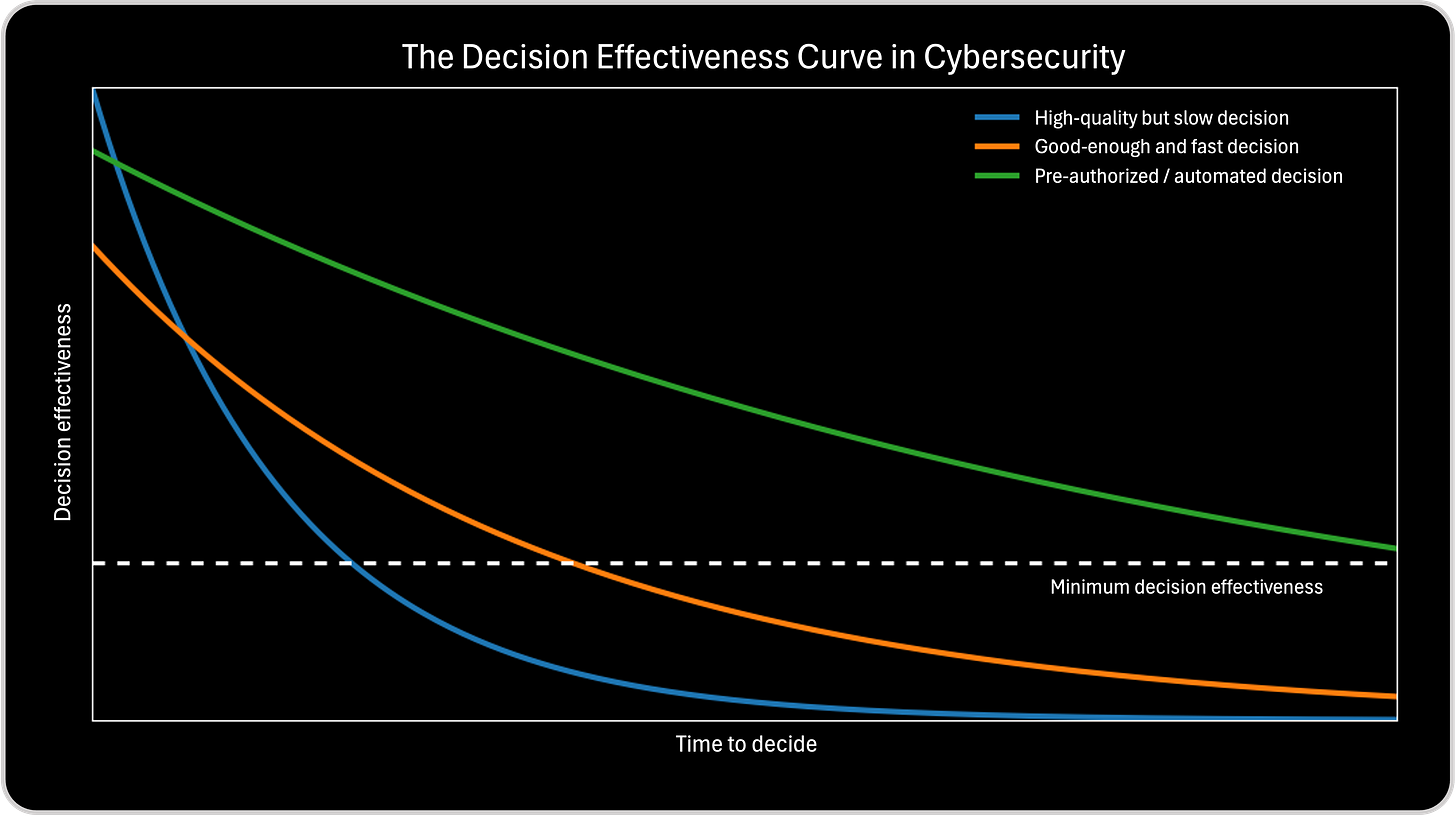

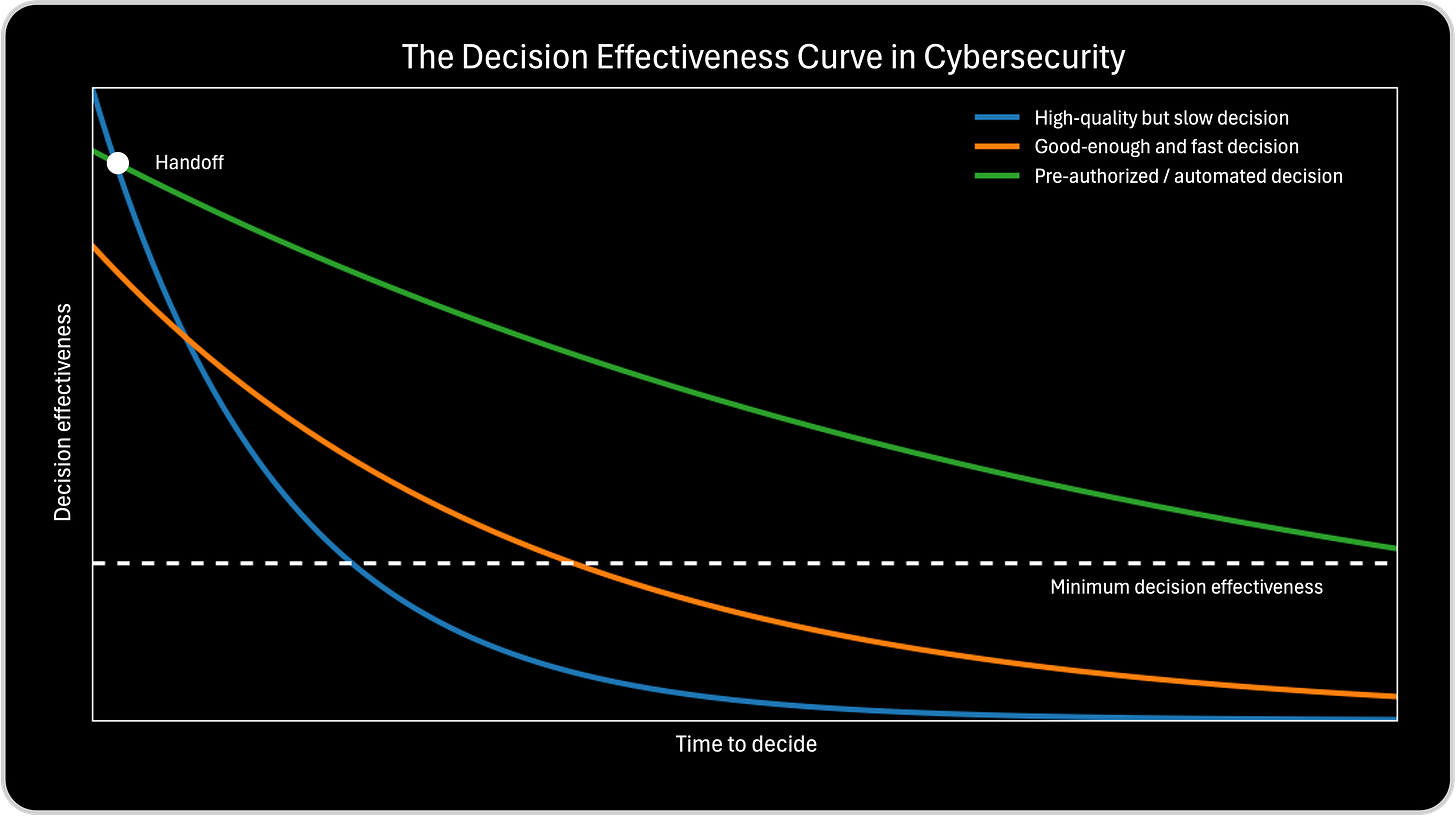

The Decision Effectiveness Curve in Cybersecurity

I use the Decision Effectiveness Curve in Cybersecurity to make the race for an effective decision visible. In an adversarial environment, decisions are not evaluated in isolation, they are evaluated against the attacker’s pace. The curve exists to show why timing, not just correctness, determines outcomes, and why every decision competes against a moving opponent. Its purpose is not to introduce another metric or maturity model, but to surface a reality that is usually implicit and underestimated: every decision has a half-life, and in cybersecurity that half-life is often measured in minutes, not days.

The chart that follows visualizes this race. The horizontal axis represents how long it takes an organization to decide, including analysis, validation, escalation, and approval. The vertical axis represents decision effectiveness, the ability of a decision to materially change the outcome. The critical insight is that these two dimensions move in opposite directions. As time passes, even as understanding improves, effectiveness decays because the attacker is still running. In this race, information can increase while advantage is being lost, and the winner is determined not by who knows more, but by who decides while the decision can still shape the result.This visual matters because it makes visible something that is usually hidden in post-incident reviews. Organizations tend to evaluate decisions based on correctness and justification. The chart shifts the lens toward timing. It shows that a decision can be correct, well reasoned, and defensible, yet still fail because it arrived after the window of influence closed. In cybersecurity, effectiveness is not determined only by what you decide, but by when you decide.

I use this curve to reframe how we think about decision making. Most organizations assume that better information naturally leads to better outcomes. The curve shows why that assumption breaks down under adversarial pressure. As confidence increases, time is simultaneously being consumed, and the attacker is actively reshaping the environment. Decision effectiveness and analytical confidence often move in opposite directions.

The three curves in the chart represent three different decision-making modes that are common in cybersecurity operations, and each one leads to very different outcomes under time pressure.

The first curve represents high-quality but slow decisions. I use this to illustrate how organizations can follow every process, validate every signal, and still lose. These decisions are careful, defensible, and analytically sound, but they arrive after attacker freedom of movement has already expanded. By the time action is taken, containment becomes damage control. This curve explains why teams can make the “right” decision and still experience a breach.

The second curve represents good-enough and fast decisions. This curve helps explain the discipline of acting under uncertainty. These decisions are made with sufficient but incomplete information and accept some risk of adjustment in exchange for speed. They arrive early enough to constrain the attacker, reduce blast radius, and preserve optionality. This is where decision effectiveness is maximized in most real-world environments.

The third curve represents pre-authorized or automated decisions. This is where the conversation shifts from operations to governance. These decisions are effectively made before the incident occurs, when intent, thresholds, and trade-offs can be defined calmly. When conditions are met, action happens immediately, without debate. This is not about removing human judgment, but about executing human decisions at machine speed.

Together, these curves make one thing clear. Cybersecurity is not a competition for perfect knowledge. It is a race between attacker action and defender decision making. The Decision Effectiveness Curve helps leaders see that speed is not recklessness, and that governance, data quality, and methodology exist to preserve effectiveness, not to slow decisions down.

The Minimum Decision Effectiveness Line and the Overtake Point

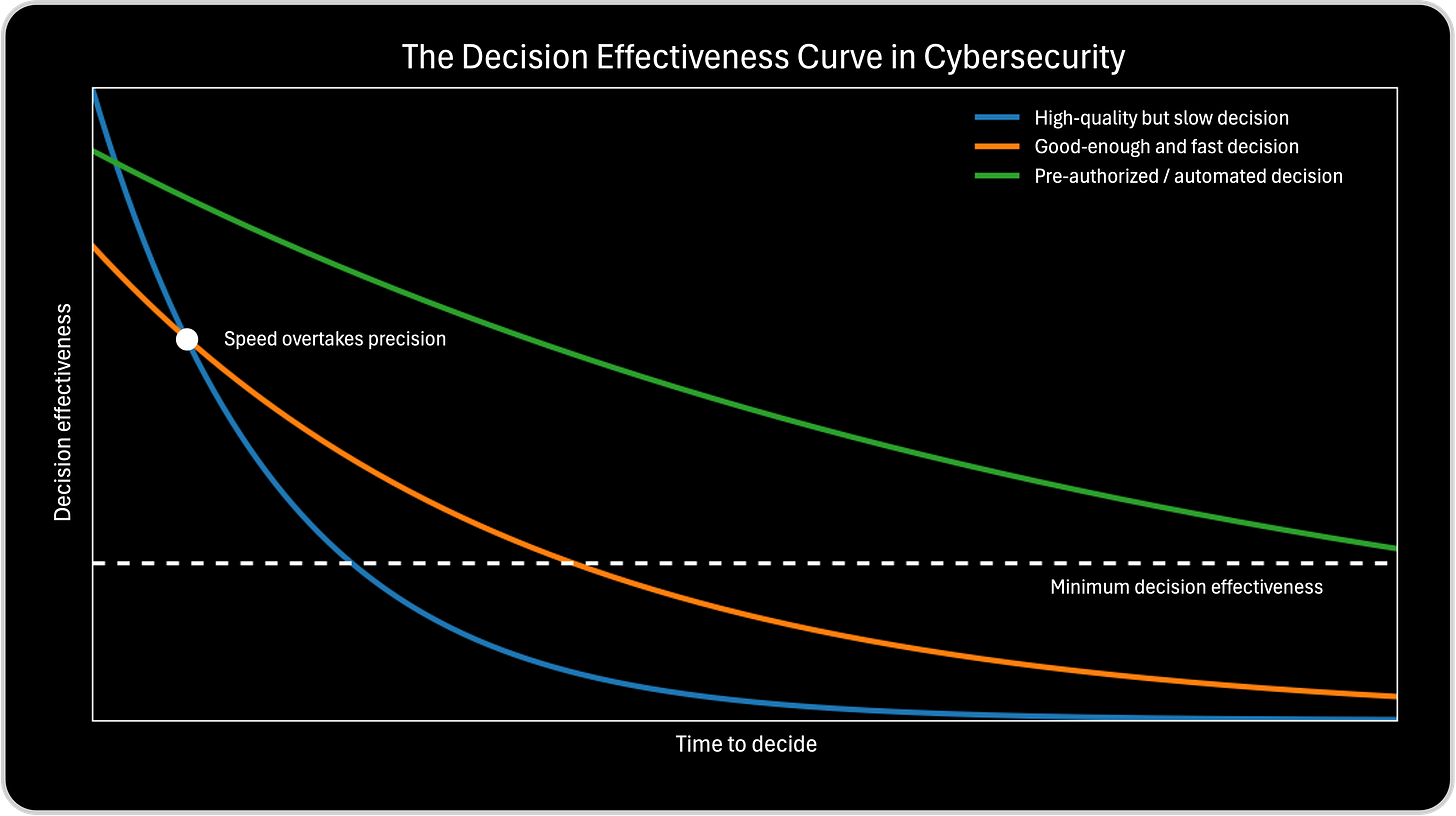

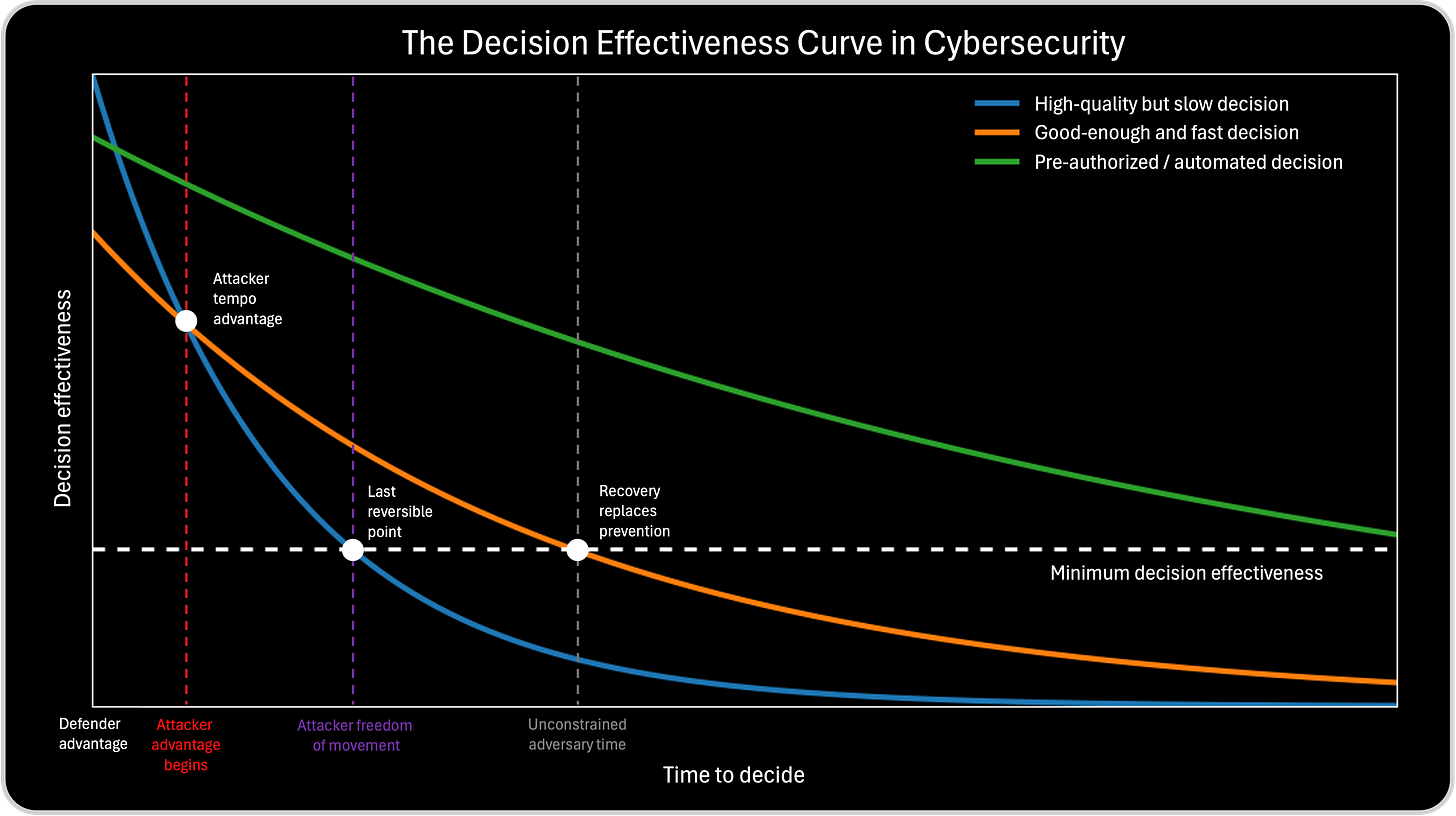

The intersection of the blue and orange lines in this chart is the most important teaching moment, because it marks the instant where speed overtakes precision.

At the point where the good-enough and fast decision curve crosses above the high-quality but slow decision curve, the balance of decision effectiveness shifts. Before this intersection, taking more time to analyze still improves outcomes. Additional context, validation, and certainty increase the likelihood that the decision will meaningfully change the situation. In this phase, precision still has value. At the intersection, both decision approaches deliver the same level of decision effectiveness. This is the tipping point. From this moment on, the attacker’s continued movement outweighs the benefits of further analysis. The environment is changing faster than the organization’s ability to refine its understanding

After the intersection, every additional second spent deliberating reduces overall effectiveness. The slow, high-quality decision continues to improve in confidence and justification, but it loses its ability to influence the outcome. Meanwhile, the fast, good-enough decision remains more effective because it arrives while defensive options still exist. In cybersecurity terms, this intersection explains why teams can be right and still lose. Waiting for full confirmation, perfect attribution, or complete consensus pushes decisions past the crossing point, where containment turns into remediation and prevention becomes response.

This is also why attackers do not need perfect execution. They only need defenders to delay long enough to cross this intersection. Once that happens, the attacker gains freedom of movement, and the defender’s best decisions arrive too late to matter. The intersection is not a failure point. It is a decision deadline. Recognizing where it sits for different types of risks is what separates organizations that contain incidents early from those that manage consequences afterward.

Below the intersection sits another critical boundary: the minimum decision effectiveness line, shown as the dashed horizontal line. This line represents the point at which decisions may still be technically correct, but no longer materially change outcomes. Below this threshold, actions are reduced to recovery, disclosure, and damage control. The dashed line makes explicit that not all decisions are equally valuable at all times, and that effectiveness has a floor.

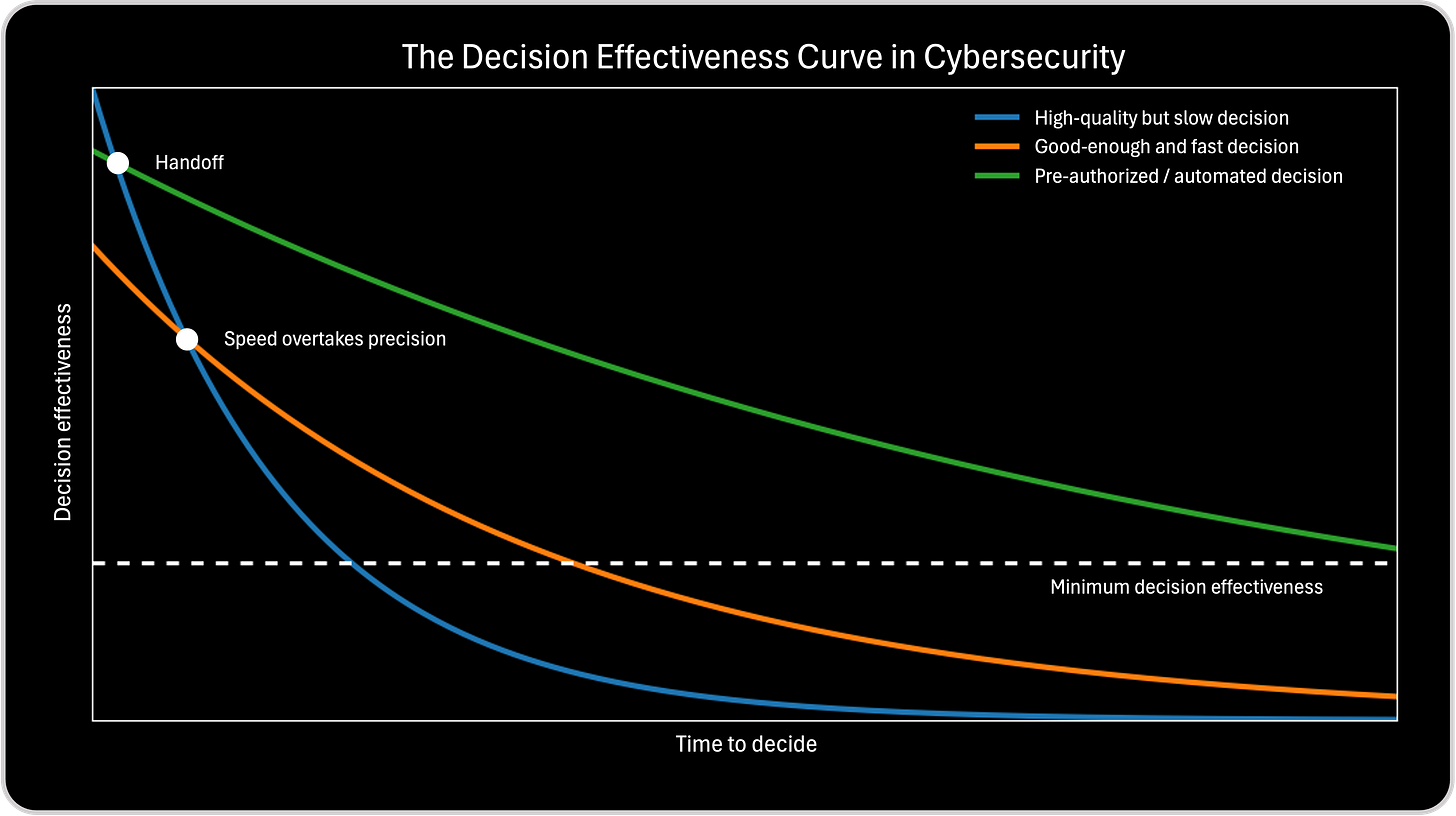

Why the Green Curve Can Intersect the Blue Curve (and Why That’s OK)

The green curve intersecting the blue curve does not mean that pre-authorized decisions become less effective than slow, high-quality decisions.

It means something more subtle and more realistic. The blue curve represents human decisions made during the incident that improve in analytical quality over time but lose effectiveness because of delay. The green curve represents decisions whose intent was defined in advance, but whose execution impact still decays as the environment changes. At very early moments, a slow, high-quality human decision can briefly appear more effective than a pre-authorized action because the situation is still constrained and human judgment can add nuance. This is the moment where blue can sit above green.

But this advantage is fragile and short-lived.

The key distinction is that the green curve does not rely on ongoing deliberation. Even if it intersects the blue curve early, it decays far more slowly, because it is not exposed to escalation delays, consensus seeking, or validation loops. So the intersection is not a competition. It is a handoff.

The moment where the green curve intersects the blue curve teaches this: Even when human judgment is temporarily superior, time still erodes its advantage. After that point, the green curve remains above the blue curve because:

The decision was already made

Execution happens immediately

Attacker freedom of movement is constrained earlier

In contrast, the blue curve continues to fall because each additional unit of precision is purchased with time, and time is being used by the attacker.

Why the Green Curve Still Avoids the Overtake Race

The critical overtake point in the chart is not green vs blue. It is orange vs blue. That’s where speed overtakes precision under live decision pressure.

The green curve sits outside that race because:

It does not depend on real-time deliberation

It does not wait for confidence to peak

It does not cross a “decision moment” during the incident

Even if it intersects the blue curve early, it never participates in the speed-versus-precision tradeoff that defines the blue-orange intersection.

That’s the conceptual difference: The green curve may intersect the blue early, but it never competes in the same race. Blue decisions are made under pressure. Green decisions were made before the pressure existed.

Attacker Advantage: When Time Switches Sides in the Race Against the Attacker

This chart shows that attacker advantage is not a single event or a sudden failure. It emerges as a race dynamic, where time gradually switches sides. From the moment an intrusion begins, defenders and attackers are moving in parallel, but not at the same speed. One side is racing to decide. The other is racing to exploit.

At the start of the race, defenders still control the pace. Signals are fresh, options are open, and decisions can meaningfully change outcomes. But as time passes, the attacker keeps advancing while defenders slow themselves down with analysis, validation, and coordination. The race becomes uneven long before any obvious failure occurs.

The point labeled attacker advantage begins marks the moment when attacker tempo overtakes defender decision speed. From here on, the attacker is no longer reacting. They are setting the pace. Defenders can still win the race, but only by accelerating decisively. Delay at this stage is not neutral. It is lost ground.

As the race continues, the attacker enters a phase of freedom of movement. Lateral movement, privilege escalation, and persistence become easier because the defender is now running behind. This is the last stretch where defenders can still catch up. The chart makes this visible as the final window where decisions remain reversible and impact can still be limited.

Once the race reaches unconstrained adversary time, the finish line has effectively been crossed. Defender decisions still happen, but they no longer determine the outcome. They manage consequences. The dashed line of minimum decision effectiveness marks this boundary clearly. Below it, the race is over. Time has fully switched sides.

Seen through the lens of a race, cybersecurity is not about perfect strategy or flawless execution. It is about tempo control. Attackers win by continuing to move while defenders hesitate. The organizations that consistently contain incidents early are not those that know more, but those that decide while they are still ahead in the race.

In cybersecurity, time is always contested. And the moment it switches sides, even the best decisions arrive too late to matter.

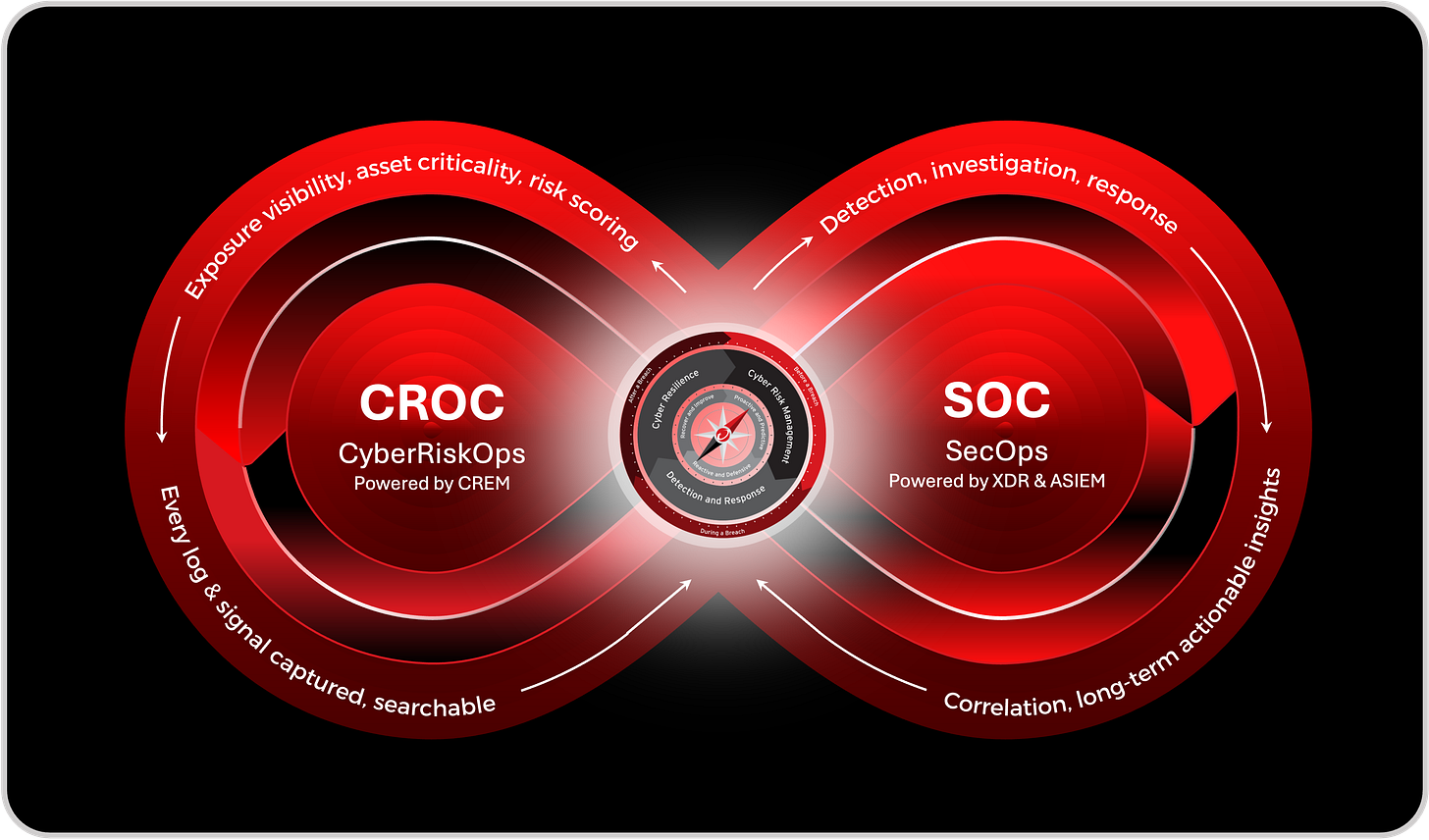

From the Race to the Loop: How CyberRiskOps Reclaims Time

The race against the attacker cannot be won incident by incident. Even the fastest response eventually loses if every decision starts from zero. This is where CyberRiskOps changes the game. Instead of treating cyber defense as a sequence of isolated races, CyberRiskOps turns speed into a structural advantage by embedding decisions into a continuous defense loop.

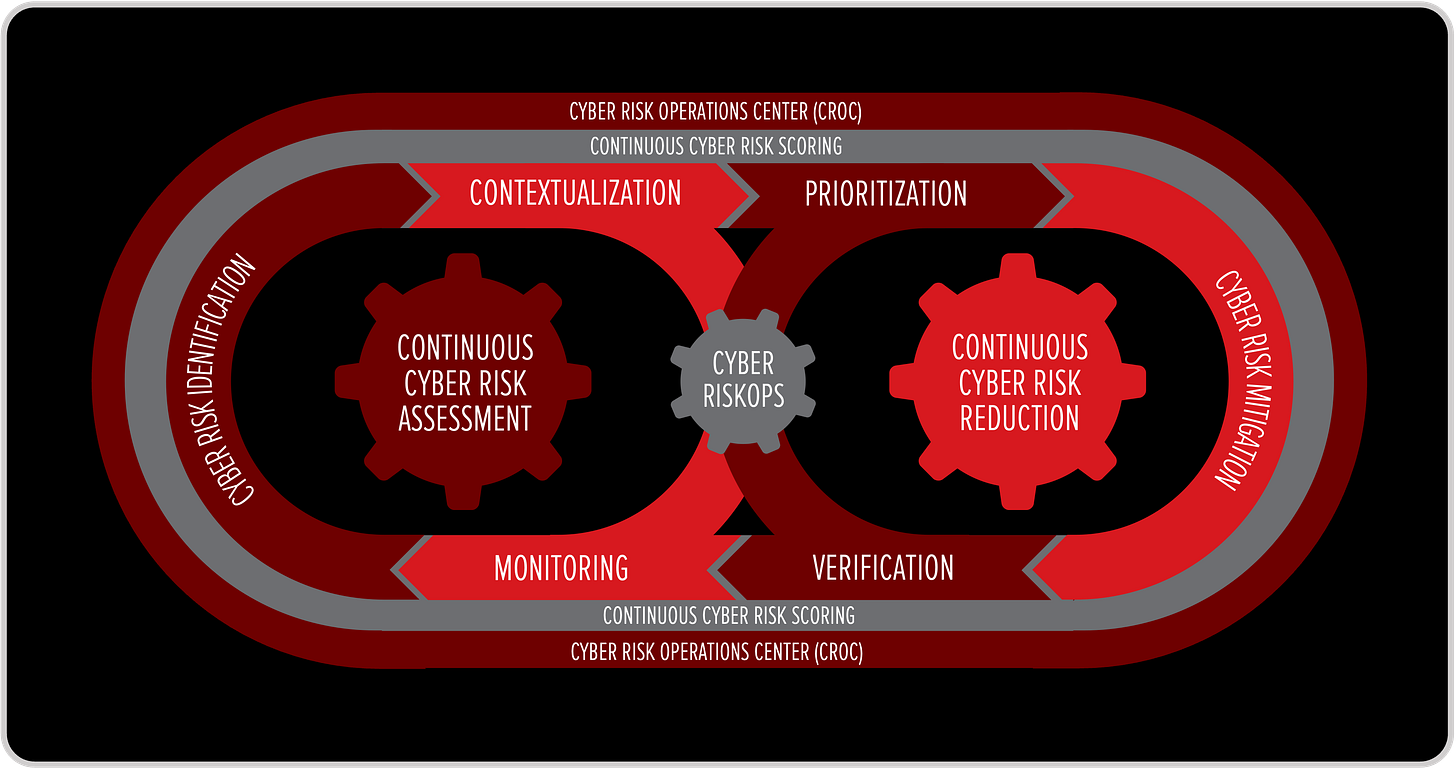

At the heart of this model sits the CROC, the Cyber Risk Operations Center. Unlike a traditional SOC, which is optimized to react to alerts and incidents, the CROC is designed to operate the race before it starts. Its role is not limited to detection or response. It continuously translates exposure, asset criticality, and risk signals into decision-ready context, so that when the SOC needs to act, the decision has already been framed. This is how the continuous defense loop closes the timing gap. On one side of the loop, Cyber RiskOps focuses on before-the-incident decisions: exposure visibility, asset importance, risk scoring, and prioritization. This is where intent is defined. Which assets matter most. Which behaviors justify automated action. Which trade-offs are acceptable under pressure. These decisions are made calmly, upstream, when time is still neutral.

On the other side of the loop, the SOC and SecOps execute that intent at speed. Detection, investigation, and response are no longer slowed by debate or uncertainty about priorities. Signals arrive already enriched with risk context. Actions are aligned with pre-approved thresholds. What looks like speed in the SOC is actually the result of decisions that were made earlier, in the CROC. The continuous loop ensures that learning flows both ways. Every incident, investigation, and response feeds back into Cyber RiskOps. Risk scores are adjusted. Assumptions are refined. Guardrails are updated. Over time, this tightens the loop and shifts the decision curves left, reducing the space where attacker advantage can emerge.

Seen through this lens, the continuous defense loop is not just an operational model. It is a tempo control system. It ensures that defenders are not constantly sprinting to catch up, but instead setting the pace by deciding in advance and executing decisively. This is the strategic alignment between CyberRiskOps, CROC, and the SOC. The CROC governs intent. The SOC enforces it. The loop between them turns cyber defense from a series of desperate races into a sustained capability to stay ahead of the attacker.

In a world where attackers only need to be faster than our decision-making process, the most reliable way to win is not to run harder during the incident, but to close the loop so tightly that the race never fully begins.

Castro, J. (2025). Cybersecurity Paralysis When the Cyber Brain of the Organization Breaks. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/397927310 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.25955.00802/1

Castro, J. (2025). Artificial Intelligence (AI) vs Artificial Instinct (Ai), The Distinction Cybersecurity Can’t Afford to Ignore. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/397834714 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.31096.30725

Castro, J. (2024). From Reactive to Proactive: The Critical Need for a Cyber Risk Operations Center (CROC). ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388194441 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.27408.93445/1

Castro, J. (2025). Cyber RiskOps: Bridging Strategy and Operations in Cybersecurity. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388194428 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.36216.97282/1

Castro, J. (2024). Integrating Cyber Risk Management to your Cybersecurity Strategy: Operationalizing with SOC & CROC. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388493453 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.30164.72328/1

Castro, J. (2024). Integrating NIST CSF 2.0 with the SOC-CROC Framework: A Comprehensive Approach to Cyber Risk Management. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388493049 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.13387.50720/1

Castro, J. (2025). Cyber Risk Operations Center (CROC) Process and Operational Guide. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389350613 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.19164.09600

Castro, J. (2025). What Is Strategy in Cybersecurity? Rethinking the Way We Lead, Protect and Adapt. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393674625 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.16703.42409

Castro, J. (2024). What Cybersecurity Can Learn from Glucose Management in Diabetes. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388528830 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.14003.54568/1

Castro, J. (2025). Introducing the CROC Levels: Operationalizing Cyber Risk Management. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/393333383 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.31393.31841

Castro, J. (2025). How a Cyber Risk Index (CRI) Can Be Used as a KPI in Your Cybersecurity Strategy. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389001302 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.32915.18728

Castro, J. (2025). Cyber Risk Operational Model (CROM): From Static Risk Mapping to Proactive Cyber Risk Operations. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/390490235 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.15956.92801

Castro, J. (2025). Cyber Risk Should Not Be Treated — It Should Be Operationalized. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/389991463 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.12429.45289

Castro, J. (2024). Safely Sailing the Digital Ocean with the Cybersecurity Compass. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387410177 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.20696.00003

Castro, J. (2025). Threat Hunters vs. Cyber Risk Hunters: Two Sides of Modern Cybersecurity. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/395721548 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.20329.35688

Castro, J. (2025). Umbrellas, Storms, and Cyber Risk: Why Threat Management Is Not Risk Management. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/396695719 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.24818.98240

Castro, J. (2024). Strategic Cyber Defense: Applying Sun Tzu’s Art of War Lessons to the Cybersecurity Compass. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387410535 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.25085.68327

Castro, J. (2024). A Common Language for Cybersecurity. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/387505866 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.31894.05448

Castro, J. (2024). Safely Sailing the Digital Ocean with the Cybersecurity Compass. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/388729549 DOI:10.13140/RG.2.2.20696.00003